For many foreigners, the extent of their knowledge of Belarus is through the politicized performances of Belarus Free Theatre. But is all Belarusian culture political? Does it even have to be?

“The last dictatorship in Europe”[1]. Originally coined by former US Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice in 2006, this description of Belarus tends to frame all current discussion about the country[2]. While a distinct country with its own language and history bordering Russia, Ukraine, and the Baltic States, the persistent popularity of the phrase in foreign media means that the entirety of Belarus has been equated with a single man: Aliaksandr Lukashenka, its controversial President since 1994. How can we pierce this veil of political catch-phrases and cultural stereotypes, and get closer to glimpsing the diversity and nuance of contemporary Belarusian experience?

“The last dictatorship in Europe”[1]. Originally coined by former US Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice in 2006, this description of Belarus tends to frame all current discussion about the country[2]. While a distinct country with its own language and history bordering Russia, Ukraine, and the Baltic States, the persistent popularity of the phrase in foreign media means that the entirety of Belarus has been equated with a single man: Aliaksandr Lukashenka, its controversial President since 1994. How can we pierce this veil of political catch-phrases and cultural stereotypes, and get closer to glimpsing the diversity and nuance of contemporary Belarusian experience?

Beyond Lukashenka

Culture has been how many foreigners first learn about Belarus, particularly in recent years. “We all know that art is not truth,” Picasso said in 1923. “Art is a lie that makes us realize the truth, at least the truth that is given us to understand”[3]. However, at least for the international community, the country’s independent artistic life seems to exclusively reside in the highly political performances of Belarus Free Theatre. Founded by Natalia Kaliada and Nicolai Khalezin in 2005, the group’s visceral performances are often explicitly critical of Lukashenka’s regime. Critically acclaimed abroad while simultaneously operating underground in their native Minsk, the group abruptly shifted course in 2010, when Khalezin and Kaliada were imprisoned along with the other protestors demonstrating against Lukashenka’s re-election on 19 December[4]. In the years since their release, Belarus Free Theatre has become a “two-headed beast”, with some members “doing plays in the UK with British, Belarusian and international actors”, while others continue “the work of their permanent ensemble in Minsk where plays are continually developed, rehearsed and performed[5]”.

Because details regarding the country´s broader artistic life remain essentially silent in foreign news media, international audiences and readers tend to assume all Belarusian artists are political like the bold and outspoken Belarus Free Theatre. But is this an accurate assessment? What is the actual activity of other Belarusians, both within the country and abroad? What are Belarusians doing in artistic disciplines besides theatre, and what insights about Belarus can we learn from their art?

“Politics kills art”

“I have more artistic opportunities here in Minsk,” says Belarusian artist Pavel Voinitski, during a Skype interview on 27 March. “I do not feel like I am in a jail.” As a contemporary artist, Vonitksi believes Belarus offers a number of practical advantages to pursue his work. “I own a cheap studio--$100 a month here in Minsk, in comparison to $1000 a month in Toronto for even the small one,” he says. “I also have a good social network here, as well as my family. I consciously choose Belarus as a place for living and doing my art.”

Belarus´ geographic proximity to Europe, Russia, and Asia also stimulates his creative practice, and he travels internationally as frequently as he can. “I simply can’t imagine my ´artistic self´ without including my experiences abroad,” he says. “It’s perfect to work somewhere as a guest artist, or as a participant of an exhibition. There are no borders, no distances in contemporary art.” However, he also says that he personally does not like to be far away from Belarus for a long time. “My loved ones live here, and I prefer to be with them.”

After receiving his PhD in sculpture from the Belarusian State Academy for the Arts, Voinitski took post-graduate courses in Canada at Concordia University (Montréal) and York University (Toronto). The 40-year-old artist has had his work included in international exhibitions in Cairo and Beijing, and in Minsk he recently curated the work of Vladimir Zhbanov. Voinitski also writes for a number of Russian and Belarusian arts journals, such as NoMI (St. Petersburg), Architecture, Construction, Design (Moscow), and Art (Minsk).

His current interest lies in practicing “sculpture in an open field.” He cites the work of Richard Serra, Krzysztof Wodiczko, Hans Haacke, and others as being particularly influential on his own art--people who questioned public and social spheres. “It´s not interesting to work just with traditional sculptural forms, materials, or meanings,” Voinitski affirms. “There are some social things that should also be sculptured.”

“I like to collaborate with like-minded persons,” he goes on to say, “so a couple of my more recent works were produced as a kind of collective project with Belarusian and international artists. For me, this is the creation of art-objects or art-spaces interacting within a specific context and community,” he explains.

While Voinitski respects and admires his contemporaries in Belarus Free Theatre, linking his own art with contemporary Belarusian politics does not interest him. “I am not a fan of Lukashenka – I have never voted for him,” he admits. “But the state is the apparatus of oppression anyway; it does not matter whether it is autocratic or liberal. Lukashenka and his regime are not an exception, and the best way for me to survive as an artist is simply to ignore those pro-state contexts.”

For Voinitski, the real challenge facing Belarusian art is the domination of traditional post-Soviet culture, particularly the stylistic elements of Socialist realism, despite the country´s independence. “To propagandize new models, more contemporary concepts of public space and sculpture,” he says passionately, “that’s my personal fight. I´m trying to do this in my writing, and practically in my sculpture.”

While previously he’s done some “ironic works related to the current propaganda,” Voinitski feels that it is more proactive to use a kind of Aesopian language of universality in art. “Because politics kills. Including art,” he adds. “Personally, I know some colleagues who work with political issues in their work,” he continues. “However, their art looks export-oriented. It’s not relevant inside Belarus.”

“Politics is not an interesting subject”

“In Belarus, I was never a free artist,” says Olja Gorohova, a Belarusian visual artist currently living in Oslo’s Majorstua district. Having lived abroad since 2009 and only returning to Belarus to visit family during holidays, she never intends to return. “I feel that it was a good decision to go abroad,” she says. “Now I am more happy. After two weeks of visiting, I´m dying there.”

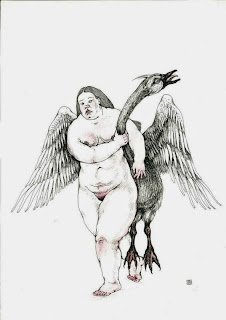

Born in the small village of Moroski near Molodechno, 30-year-old Gorohova told me during an interview on 2 April how she creates decorative and figurative pieces using various materials. Recently, she completed a set of miniature Sumo wrestlers in porcelain. Now she´s begun a sequence of drawings inspired by Greek mythology, using these familiar stories to create a new context for herself. In Olja’s drawings, Leda is earthy and strong against the swan, not the romanticized victim traditionally represented. “Before, my work was more intuitive,” she explains. “Now I´m interested in making clearer concepts, more logical sources of inspiration.”

Leda by Olja Gorohova. Pencil on paper, 2013, Oslo.

She studied ceramics for four years at the Belarusian State Academy of the Arts in Minsk, but the curriculum left her restless and frustrated. “I wanted to study contemporary art, but Belarus is stuck in the past”, Gorohova says. “We didn´t have any new programs or books. We didn´t even have internet before my last year there.” Gorohova stopped before completing her fifth and final year there.

“In Belarus, you get a grant to study for free,” she explains, “but in exchange you must work at a place offered to you by the state after finishing university.” For Gorohova, this meant “a ceramics factory in a village where most of the inhabitants are alcoholics.” Rather than accept the traditional path, Gorohova chose instead to pursue her childhood dream of living abroad. She saved up money for a year, working as a painter at a monastery by day, and then by night cleaning dishes at a strip club. “It was a funny contrast,” she says, rolling her eyes with a smile.

Her first destination was the Czech Republic, chosen because of its affordability, her ease in learning the language, and because she “wanted to feel free.” For the next three years she studied ceramics and porcelain at the Academy of Arts & Architectural Design in Prague. In stark contrast to her previous studies in Minsk, this period was “all about concept.” “My Belarusian academy was very conservative, and so the exercises were also very conservative,” she says. “It was just craft, technique. No one cared about the concept. In Prague, it was the total opposite.”

Next, Gorohova went to Spain for one year on an internship in sculpture at the Polytechnic University of Valencia, before moving to Norway five months ago. Struggling with the language and getting her work displayed in a Norwegian gallery, Gorohova currently works as a house-cleaner through her immigrant´s work visa. “It´s economically attractive, but Norwegian society is also pretty conservative,” she observes. “I miss the energy of Prague, where art always seemed to be two steps ahead. Here in Oslo, it feels like a smaller version of what happened in Europe ten years ago.”

Gorohova has never considered herself an activist, and since leaving Belarus five years ago has not kept up with news related to Lukashenka or his government. “I am not interested in what happens in Belarus politically,” she says. “Politics is not an interesting subject.” Lately, however, it seems she has a touch of homesickness. She is reading more Belarusian literature, and misses speaking her native language. Nonetheless, she recognizes the scope of these feelings. “It´s very easy to love Belarus from the outside,” she says. “I was very unhappy there, all the time trying to reject Belarusian culture, dress, behavior,” she goes on. “I have such a difficult relationship with the country. Everybody does, with Belarus.”

Placing these visual artists’ work alongside Belarus Free Theatre, the country´s contemporary artistic landscape immediately becomes more diverse in form and content. Whether working within the country or living abroad, Belarusian artists are wrestling with a variety of themes in their work, not just the politics or persona of Lukasheka. Artists such as Voinitski and Gorohova are not interested in "the last dictatorship in Europe" as a subject; they have other truths they want their audiences to understand.

References :

[1] Stephen Mulvey, “Profile: Europe´s last dictator?”, BBC News, 10 September 2001.

[2] Andrej Dynko, “Belarus - Europe´s Last Dictatorship,” New York Times. 16 July 2012.

[3] Alfred H. Barr, Jr., Picasso: Fifty Years of His Art (Arno Press, New York), 1980.

[4] Roland Oliphant, “Police ´threatened to rape´ Belarus Free Theatre director after election protest,” The Telegraph. 25 December 2011.

[5] Belarus Free Theatre website: www.belarusfreetheatre.com/about/.

Picture : Lenin Leaves Muzeum by Pavel Voinitski. Performance, mixed media, 2010, Minsk.

* Artist, teacher, writer and the Artistic Director of Ensemble Free Theater Norway, Oslo.

Consultez les articles du dossier :

- Dossier #67 : «Portrait du Bélarus»

À quoi ressemble le Bélarus en 2014 ? Vingt ans après la première élection d’Aliaksandr Loukachenka à la présidence de la République, ce dossier veut porter un éclairage nouveau sur les…