Synthesis of the joint conference organized by Eastern Circles and the Caucasus Research Resource Center – Armenia, with the support of Diplomatie magazine.

Three years after the Velvet Revolution, which turned a former journalist Nikol Pashinyan into Prime Minister, Armenia was shaken by a rekindled war in Nagorno-Karabakh and an attempted coup d’état. Eastern Circles discussed the current situation in the country, its relations with Russia and Turkey, the development of domestic reforms after the Velvet Revolution, and the challenges faced by the government in Yerevan with two expert speakers: Taline Papazian, political scientist and professor at the University of Aix-Marseille, as well as Ella Karagulyan, program manager for the Data Initiative and the Caucasus Barometer for Armenia’s Caucasus Research Resource Center (CRRC).

Three years after the Velvet Revolution, which turned a former journalist Nikol Pashinyan into Prime Minister, Armenia was shaken by a rekindled war in Nagorno-Karabakh and an attempted coup d’état. Eastern Circles discussed the current situation in the country, its relations with Russia and Turkey, the development of domestic reforms after the Velvet Revolution, and the challenges faced by the government in Yerevan with two expert speakers: Taline Papazian, political scientist and professor at the University of Aix-Marseille, as well as Ella Karagulyan, program manager for the Data Initiative and the Caucasus Barometer for Armenia’s Caucasus Research Resource Center (CRRC).

The conference was moderated by Dylan van de Ven, Eastern Circles’ editorial team member. The present synthesis covers the interventions of the two experts as well as the presentations made by Eastern Circles’ editorial board.

Post-revolutionary changes

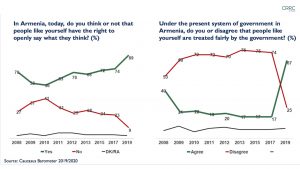

The CRRC social survey data show a feeling of positive democratic evolution in Armenian society. Thus, Armenians feel that they have more liberty to speak their mind, are treated more fairly by the authorities, and perceive lower corruption levels since 2018. At the same time, institutional reforms languish, partly as Armenia lacks qualified individuals following decades of brain drain(1): over 1 million of Armenians have left the country since 1989 and 7 million Armenians live abroad, compared to only 3 million within the country(2).

Those Armenians which remain have grown accustomed to their political freedoms acquired since 2018, and especially after the second free and fair parliamentary elections since 1999. Yet, the war in Nagorno-Karabakh in the fall of 2020 shifted citizens’ priorities in favor of security and stability over democracy – particularly as a clear line between democracy and populism is hard to draw. The war has further brought along an institutional crisis, thereby endangering the state itself and the durability of democratic reforms.

Public attitudes toward the government and the army

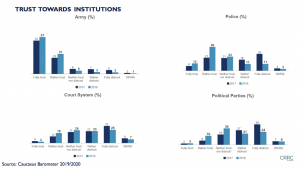

Public trust in the army is high, even following the military defeat in Nagorno-Karabakh last fall. However, Armenians draw a clear distinction between the soldiers and the institution of the army and its leaders, who are expected to remain politically neutral according to the constitution. This helps explain why the failed coup d’état by the army this February 25th resulted in demands of the Prime Minister for the Chief of Staff Onik Gasparyan to resign, instead of his own resignation.

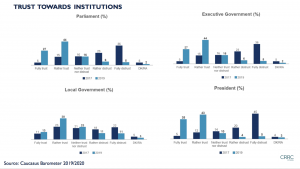

Despite the loss of the surrounding territories of Nagorno-Karabakh, the introduction of Russian peacekeepers in the enclave, a deteriorating economy owing to COVID-19 and fighting, and an increasing dependence on Russia, according to Ella Karagulyan, Armenia’s Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan remains the most popular politician in the country so far. While levels of trust in his government are low, they are still higher than in any other previous government. At the same time, trust in local government, the judiciary and the political parties did not improve much since 2017.

Nagorno-Karabakh war

Nagorno-Karabakh historically occupied the central stage in Armenian politics since the country’s independence in 1991, especially as a significant number of traditional political elites hail from the Karabakh enclave. Yet, this is not the case for Nikol Pashinyan who has faced, until last autumn, criticism for achieving scant progress in the conflict resolution. Tellingly, his 2018 “political platform” barely mentions the Nagorno-Karabakh crisis.

The Azeri-Armenian conflict over its territory was settled by 1994 ceasefire agreement. The Madrid Principles prepared by the Minsk Group co-chairs (the OSCE, France, Russia and the US) in 2007 were meant to pave the way for a peaceful settlement of the conflict. However, they did not solve the enclave status - setting a time bomb which went off in September 2020. Today, Armenia must cope with the new status quo of the November ceasefire agreement, negotiate a return of the prisoners of war (POWs) remaining in Azerbaijan(3), and manage the flow of displaced persons from Nagorno-Karabakh, who can expect more help from civil society and the diaspora than from the state. While Armenia and Azerbaijan, respectively, increased their dependence on Russia and Turkey through war, a direct dialogue between them to find a permanent solution to the NK status looks unlikely.

Rehabilitation of the pre-revolutionary political elite

The on-going anti-Pashinyan protests in Yerevan raise the question about a return of the “Karabakh clan” political elites ousted by the Velvet Revolution: former presidents Robert Kocharyan and Serzh Sargsyan. At the peak of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict in October 2020, Kocharyan and Armenia’s first President Levon Ter-Petrosyan organized a joint comeback by requesting Pashinyan to send them as Armenia's official envoys to Moscow to negotiate for peace. Their request was not fulfilled. Since then, the two have been capitalizing on their former positions of presidents, seeking legitimacy to take advantage of the on-going political crisis in Yerevan. Kocharyan has been very vocal about his intention to run in the next elections, although he is still facing trial on charges related to his mass repression of March 2008 demonstrations. Ter-Petrosyan, is staying in the background, but recently managed to hold direct discussions with Russian Ambassador to Armenia Sergey Kopyrkin over the sensitive question of the POWs.

Finally, political instability has created a momentum for Serzh Sargsyan, who gave his first interview since he was overthrown by Pashinyan-led Velvet Revolution in 2018. Sargsyan started his comeback by accusing Pashinyan of treason and criticizing the ceasefire conditions(4).

The role of third countries and the future of the Minsk Group

While local authorities in Stepanakert welcome Russian troops in NK, for Yerevan the relationship with the Kremlin all but became even more asymmetrical and intrusive. Furthermore, Turkey has increased its influence in the region and sees the South Caucasus as an extension of the Middle East. The hopes to see Armenia’s border with Turkey opening have vanished, as the latter threw its support behind Azerbaijan during the war. Yerevan’s incessant geographic isolation will reinforce its economic dependence on Russia. This, and Azerbaijan’s increasing proximity to Turkey, reinforce the role of both Caucasian states as a geopolitical playground for Russia and Turkey, further jeopardizing their sovereignty.

The US have been absent from the region during the conflict, rendering the Minsk Group – the 1994 NK conflict settlement instrument - all but irrelevant. This plays into the hand of Moscow, which brokered the ceasefire of 2020 and deployed peacekeepers to the region. The Russian decision was made regardless of being subjected to the group’s neutrality principle as one of the three co-chairs of the OSCE Minsk Group. The November ceasefire agreement fails to even mention the Minsk Group.

Several experts(5) consider that the parallel diplomacy deployed by Moscow significantly contributed to sidelining France and the US from the conflict settlement. With attentions drawn to a tense power transition in Washington DC and a strenuous management of the pandemic, the two countries’ respect of the neutrality agreement ultimately confirmed their withdrawal from the region. Even so, contemporary Russia - confronted with a muscular Turkey - might come to revisit the new situation. Ankara was only given a permanent member status in the 1994 OSCE arrangement of the Minsk Group. Now it is Russia’s main competitor for regional influence. With the West eager to restore full economic cooperation with Russia and talking about new security architecture in the larger European region, it remains to be seen if Moscow may seek to reanimate the Minsk Group once its peacekeeping mission comes up for renewal in 5 years’ time.

Notes:

(1) Tigran Yégavian, Arménie : à l’ombre de la montagne sacrée, Collection l’âme des peuples, Nevicata, Paris, 2015.

(2) Monique Bolsajian, The Armenian Diaspora: Migration and its Influence on Identity and Politics, University of California, 2018.

(3) Ani Mejlumyan, « Two months after war, dozens of Armenian POWs remain in Azerbaijani captivity », Eurasianet, January 2021.

(4) « Les politologues voient dans l’interview de Serge Sargsian une tentative de se justifier », Kavkaz Uzel, 19 février 2021.

(5) Vladimir Socor, « The Minsk Group: Karabakh War’s Diplomatic Casualty », Eurasia Daily Monitor, Vol. 17 Issue 168, November 2020.

* This synthesis was writen by Eléonore Garnier, Irene Sciurpa, Gabrielle Valli, Dylan van de Ven, members of Eastern Circles editorial board.