There are no signs on the façade of the organization’s building, nor on the intercom, so much so that one wonders whether the meeting place is correct. Like many others in Yerevan, the entrance is through a heavy building door. The address and code for the intercom are sent a few hours before the meeting by email or messenger. Pink Armenia is an NGO that defends the rights of LGBT+ people. It is deliberately discreet and, above all, suspicious. In 2015, its address was made public after members of the Armenian Eurovision jury made homophobic remarks about Conchita Wurst. Pink Armenia took the case to court. The media coverage of the case was such that many journalists lined up outside the NGO’s offices. Faced with this sudden publicity and not wishing to be associated with an LGBT neighborhood, the neighborhood became increasingly hostile towards the organization, forcing it to move.

There are no signs on the façade of the organization’s building, nor on the intercom, so much so that one wonders whether the meeting place is correct. Like many others in Yerevan, the entrance is through a heavy building door. The address and code for the intercom are sent a few hours before the meeting by email or messenger. Pink Armenia is an NGO that defends the rights of LGBT+ people. It is deliberately discreet and, above all, suspicious. In 2015, its address was made public after members of the Armenian Eurovision jury made homophobic remarks about Conchita Wurst. Pink Armenia took the case to court. The media coverage of the case was such that many journalists lined up outside the NGO’s offices. Faced with this sudden publicity and not wishing to be associated with an LGBT neighborhood, the neighborhood became increasingly hostile towards the organization, forcing it to move.

Yet it was this door that Maxime, a young gay Russian, pushed open to ask for help and advice. Having arrived in Yerevan in October 2022 to escape military mobilization, this native of St Petersburg stands out locally for his long hair, beardless face, and pale complexion: “When the mobilization was announced, I realized that I wasn’t psychologically fit to stay in Yerevan. When the mobilization was announced, I realized that I wasn’t psychologically fit to stay in the country and that it was physically and mentally difficult. So I realized I had to go somewhere else because I couldn’t cope there: I was always afraid to leave the house, watching the news, and was stressed. (...) I left the country by plane. In fact, unlike many people, I had a super easy flight; I just got on a plane and took a direct flight to Armenia.”

The young Russians chose Armenia because it is easier to enter without visa formalities. Since then, he has asked Pink Armenia’s legal department for help obtaining documents to allow him to stay in the country for more than just a tourist visit. Despite being 32 years old, Maxime does not speak English. The fact that Armenians speak fluent Russian was a factor in his choice of destination for exile. “I have an acquaintance from Armenia. She lives in Russia now and told me a lot about Armenia. She told me what kind of country it was, and I decided it was a good option.”

Pink Armenia has seen a surge in requests for help with the arrival of LGBT Russians. Around a hundred have contacted the association for legal advice or accommodation with a friendly landlord to get around discrimination. Maxime confides: “I feel safer here, more at ease, because I have never felt any aggression towards me. I’ve never experienced that.”

Dilemma

At the helm of Pink Armenia, which he founded in 2007, Mamikon Hovsepyan keenly observes the LGBT+ rights situation in Armenia. Far from the Caucasian El Dorado that Russian LGBTs think they have found, he is there to remind them of the reality of the local situation. He laughs as he recalls: “I remember the first few days, they said: ‘We want to organize a Gay Pride in Yerevan.’ I replied: ‘Sorry, guys, but who are you to organize a Gay Pride here in Yerevan? Is this the right time? Do we need one?’ They were in the mode: ‘We live here now, so we want to show our colors.’ I retorted: ‘Sorry... You can’t do that here! Because sometimes people come and do things and then leave. Then, we have to answer for the consequences. We don’t want that!’ ”

Mamikon, with his relaxed look and greying forties, is a well-known face in the country regarding Pink Armenia’s activism.

The dilemma for the NGO is how to help LGBT+ Russians fleeing mobilization while continuing to support the Armenian community. “Russians fleeing the war are arriving in Armenia, Georgia, and other countries. And that changes the situation here, too. There are many gay Russians who need support. Some of them have no money. Others are transgender people undergoing hormone treatment. And they have difficulty finding it here. We know that the situation is not the best in Armenia, and our transgender people also face many problems. So we have to find a certain balance,” observes Mamikon.

The NGO receives no financial support from the State, only donations, mainly from foundations supporting LGBT+ communities internationally.

Since homosexuality was decriminalized in 2003, the situation in the country has hardly changed. There is no legislation to protect against hate speech or discrimination, no recognition of civil partnerships or marriage, and even less opportunity for transgender people to have a change of civil status recognized.

“Russia has a very negative influence.”

In 2018, the Armenian Revolution raised many hopes within the LGBT+ community. The regime change and the promises had given hope of rapid societal progress, but this never materialized.

The religious nature of Armenian society partly explains its conservatism, but the influence of Russia’s big neighbor is not negligible, particularly in rural areas. Mamikon sees this in her work for Pink Armenia: “Russia has a very negative influence on us. Whether we like it or not, it also uses these political manipulations to influence the human rights situation in the country, which is a negative thing for us as an organization. Russia has laws that discriminate against LGBT people, what they call LGBT propaganda [Russian law of 2013, amplified in 2022, editor’s note]. Our politicians have tried to pass similar laws several times, but fortunately, they have not succeeded. That’s why the situation is a bit worrying.”

“Cascade” monument in Yerevan.

Compared to Russia, the LGBT rights situation in Armenia may seem better, but the reality is double-edged. While there is no state-sponsored anti-LGBT propaganda, the community lacks visibility and places to socialize, such as cafés, bars, and nightclubs. “It’s more dangerous to be gay in Russia, but, at the same time, if you penetrate a certain milieu, you discover more open, confidential places. Here, everything is very compartmentalized! For example, I can’t imagine having a relationship here. Because I can’t imagine going openly somewhere in town with a boy, for example to a café or for a walk... It might even be complicated for him if I want to meet someone. They all tell me, ' I can’t go anywhere with you because everyone knows me here.’ It stops them from living their lives. Especially with the way I look, no one wants to be in public with me,” Maxime remarks.

Maxime, Erevan.

An invisible LGBT community in Armenia

Many of Mamikon’s colleagues prefer to work in the shadows, an activism that takes place behind the scenes and moves forward cautiously. “We’re not asking for radical transformations because our strategy is, in a way, very gentle, and we want changes to be made gently,” Mamikon points out.

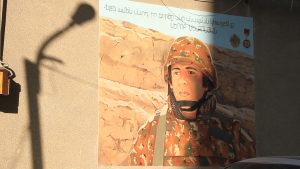

Frescoes of young Armenian soldiers killed in the fighting against Azerbaijan in 2020, Yerevan.

The explosive reality of the geopolitical situation in Armenia is also catching up with Russian exiles. The resumption of armed conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan in 2020 has created an atmosphere of latent war in Yerevan. The threat of the situation degenerating into all-out conflict is fuelling fears. “Usually, during a war, violence in society increases, and, in some cases, it is LGBT people who are targeted. Society thinks these people are not protecting their land or helping protect the country. This is one of the reasons why society does not accept them. In many cases, people hide their homosexuality and don’t talk about it. This is also a factor that makes the community’s situation more vulnerable,” Mamikon analyses.

Haik, 26, is a young gay man from Yerevan, smiling and mischievous. Although he has come out to his friends and work colleagues without encountering any problems, his face tightens up when he talks about his family: “Since I came out, we don’t talk about it with them. I haven’t encountered any homophobia for a long time outside my family...”

Since 2013, at an address also kept secret from the general public, Pink Armenia has created a community space where people can meet up, chat, drink coffee, and play cards... It’s all part of the association’s policy of taking small steps: enabling everyone to come out of their isolation, to feel accepted without risking judgment or an accusatory look, and finally to feel free, even if it’s between four walls. “Pink Armenia, first of all, gave me a space where I could meet people from the community, and I also saw many more open-minded people, which helped me blossom. Pink Armenia is like a second family that allows you to be yourself,” Haik points out before playing cards with Alice, a transgender woman.

As well as providing legal assistance and advice, the NGO also provides the services that the Armenian government deliberately fails to deliver: health information, psychological support, awareness-raising, and training for doctors in dealing with LGBT+ populations...

The impossible return

Mamikon estimates that around 200 LGBT Russians have settled in Yerevan without contacting Pink Armenia. Working mainly from a distance, they have settled in smoothly, even if the duration of their exile is linked to that of the war in Ukraine.

The massive influx of Russian exiles into the Armenian capital has caused rental prices to soar (+40% in just a few months). Landlords often prefer to rent to Russians at a higher price. This surge in housing prices affects all Armenians, but many LGBT people in particular. Some have had to find a new, more affordable flat and once again face discrimination problems. This inflation is beginning to create some tensions with new arrivals.

For his part, Maxime believes that the Russians can make an effort: “In general, when I hear talk of Russophobia in certain countries, I always say that there is no country more Russophobic than Russia itself. It seems to me that people don’t like each other very much. And they’re always trying to blame others.”

Maxime doesn’t know where he’ll put down his bags for the long term - Armenia or another country. Since leaving Russia, he can’t see beyond a week. However, he is sure that there is no turning back for him. No Russia! “I have no hope for the LGBT community in Russia at the moment. And if the regime doesn’t change, things will get even more complicated...”

Thumbnail: Poster for the NGO Pink Armenia (© Michaël Briffaud).

* Michaël Briffaud (text and photos) is a freelance journalist, currently based in Vienna (Austria) and formerly in Washington DC; he works regularly for AFP’s video bureau.

Link to the French version of the article

Translated from French by Assen SLIM (Blog)

To quote this article: Michaël BRIFFAUD (2023), “Armenia: a refuge for Russia’s LGBT+ community?”, Regard sur l’Est, 15 May.