The author of 24 heures de la vie à Tchernobyl (PUF, 2024) looks back at some little-known aspects of daily life in the Soviet Union at the start of the reforms launched by Mikhail Gorbachev.

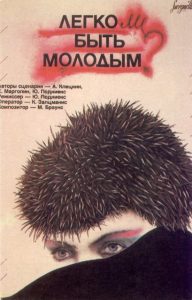

Is it easy to be young? It is the title of a documentary film shot in Riga in the summer of 1986 and released in Soviet cinemas in early 1987. It shows a group of secondary school boys and girls, some of whom (all of them boys) are on trial for wrecking a suburban train carriage on their way home from a rock music concert a few months earlier. The film broke several taboos at the time, including the violence and idleness of a youth whose comfortable lifestyle had never been enjoyed by previous generations in the USSR and the issue of drugs and premarital sex, both of which were censored by the media at the time. It immediately became a cult film, a symbol of the change of tone in the public sphere, symbolic of glasnost, a slogan sometimes confused with liberalization or an injunction to “transparency” in the USSR’s ruling bodies, when in fact, it should be translated as “saying things out loud (glasno).”

Is it easy to be young? It is the title of a documentary film shot in Riga in the summer of 1986 and released in Soviet cinemas in early 1987. It shows a group of secondary school boys and girls, some of whom (all of them boys) are on trial for wrecking a suburban train carriage on their way home from a rock music concert a few months earlier. The film broke several taboos at the time, including the violence and idleness of a youth whose comfortable lifestyle had never been enjoyed by previous generations in the USSR and the issue of drugs and premarital sex, both of which were censored by the media at the time. It immediately became a cult film, a symbol of the change of tone in the public sphere, symbolic of glasnost, a slogan sometimes confused with liberalization or an injunction to “transparency” in the USSR’s ruling bodies, when in fact, it should be translated as “saying things out loud (glasno).”

What was life like for young people in Pripyat, the satellite town of the Chernobyl nuclear power station(1), destined to become Europe’s largest power station with four reactors in operation and two more under construction at the time? This town of almost 50,000 inhabitants was located in Ukraine, but the overwhelming majority of the population spoke Russian - the lingua franca of the empire. As in all ‘nuclear’ towns, i.e., those dedicated to the atomic energy sector, life was more comfortable here than in the rest of the country.

Militarised youth: uniforms, military preparation and parades

Militarised youth: uniforms, military preparation and parades

The school day began at 8 o’clock. Pupils were obliged to wear a uniform: in 1984, girls in the last three classes (equivalent to the “lycée” in France) were allowed to replace their dress with a skirt and blouse or jacket, but it was not until 1988 that they were allowed to wear trousers, and then only in some areas of the USSR. Unlike boys, they had to cut, wash, then iron and sew their collars and cuffs every week, the cleanliness of which was regularly checked, at least in principle. As for the boys, they wore navy blue trousers and jackets throughout the country, but brown in Ukraine, made from a fabric similar to denim (the fabric used for jeans) after 1975. An emblem was sewn onto the left shoulder: for the lower grades, it featured an open textbook with a sun on a red background, and for the upper grades (from age 15), an open textbook with a sun coming out of it, on a blue background, with an atom at its center. Every Soviet teenager was reminded of the importance of nuclear energy.

Badges were sewn onto the school uniforms of Soviet schoolchildren aged 7 to 14 (left) and 15 to 18 (right) between 1975 and 1991. (source: Wikipedia)

“Basic military training” was offered to all pupils aged between 15 and 17, both in ordinary secondary schools (the most prestigious) and vocational and technical schools. These included courses in dismantling and reassembling Kalashnikov assault rifles (AK-47 and other variants). This activity led to school competitions and, for male and female champions, between districts and regions. Other courses focused on what to do in the event of nuclear, chemical, or bacteriological warfare, as evidenced by the phenomenal quantity of gas masks found on the premises of Pripyat schools and colleges after the town was evacuated on 27 April 1986, the day after the explosion at reactor number four that marked the start of the disaster(2).

The 1970s and 1980s saw a flowering of air rifle shooting ranges in the Soviet urban landscape: in 1986, Pripiat had ten of them, as many as there were gymnasiums. By registering with the social organization that ran the ranges, pupils aged between 10 and 13 could even obtain a “young shooter” certificate (and the corresponding badge), established in 1972 based on the one that had existed from 1932 to 1941 for young people aged between 13 and 17.

On 9 May 1985, for the second time after 1965 and almost forty years after 24 June 1945, when Stalin and the leading group were present, a large military parade was held in Moscow to commemorate the Soviet Union’s victory over Nazi Germany Soviet d Union’s victory over Nazi Germany. Other, much smaller “parades” took place in towns nationwide, including Pripyat, as attested by a photograph posted on a Russian social network. The event confirmed the direction taken by a regime that was relying more and more on a memorial myth, that of the Great Patriotic War, which consisted of concealing the foreign aid that the USSR had received during the Second World War and Stalin’s responsibility for the human and military cost of the defeats of 1941, to consolidate its legitimacy among the population, while concealing the losses of another war in progress, that of Afghanistan(3).

Objects, clothing, cultural products: the reign of privilege, blat, and the black market

At the time, the whole of the USSR was governed by the blat system, a word that can be translated into French as “piston,” but with a broader meaning. The political scientist Alena Ledeneva defines it as “an exchange of access favors in conditions of scarcity and a state system of privileges,” “access favors” is characterized by the fact that they were granted “at the expense of the [general] public,” in favor of the needs of one or more individuals(4). This set of informal practices amounts to a generalized bartering of goods and services between individuals from different professional backgrounds and affects all social strata. People mobilized their networks on a variety of occasions, for example, to buy

- beer of better quality than that sold in kiosks, or strong alcohol: vodka or cognac (a rare commodity in these times of virtual prohibition triggered by the anti-alcoholism measures of 1985);

- a pirate vinyl record or audio cassette (magnitizdat) of a foreign or Soviet rock band, as in a scene from Kiril Serebrennikov’s film Leto (Summer) (2018), which tells the story of the early days of the rock band Kino in Leningrad ;

- or, if you could afford it, a video cassette recorder or a walkman, the musical cassette player invented by Sony in 1979, a distant ancestor of the smartphone in this respect.

These two aircraft types could be purchased either during a business trip abroad, for the happy few (artists, sportsmen and women, and high-level political or economic leaders), or as part of a tourist trip, which was more widespread but also reserved for elite members. Aeroflot sailors and cabin crew were also likely to have access to these coveted capitalist objects.

But within the USSR, or instead in the capital cities of Moscow, Kiev (Kyiv) and Leningrad, there were also beriozki (birch) shops, where you could only pay with special ‘certificates,’ These could only be exchanged for foreign money (mainly dollars and West German marks), and offered products that could not be purchased elsewhere, including caviar and strong alcohol (Soviet products but not found on the shelves of ordinary shops), or electronic equipment, including pocket calculators(5).

In the 1970s and 1980s, they fuelled an explosion in clandestine currency exchange, practiced by valiutchiki (currency dealers), and under-the-counter sales, in other words, on the black market, of fartsovka. From 1980, Soviet officers serving in Afghanistan, a small landlocked country in southern Central Asia that the USSR had invaded on the pretext of helping a “socialist” revolution, also had access to beriozki. The term “Afghans” to designate the Soviet soldiers involved in this operation appeared in the press in 1986 and was probably spoken well before then. Official discourse referred to them as “internationalist fighters.” Ironically, it was mainly through objects that this international character existed: in the beriozki, the senior “Afghans” bought Italian jeans, video recorders, radio cassettes and walkmen produced in the West, which they then usually resold.

After the accident on 26 April 1986, another category of the Soviet working population was able to enjoy these privileges, but at a high cost to their health: the people involved in “liquidating the consequences” of the nuclear disaster, henceforth known as “liquidators” (in the masculine form, even though a small minority of them were women)(6). But that’s another story.

Notes:

(1) The name “Chernobyl” is used here, transliterated from Russian, whereas in Ukrainian, it is written and pronounced “Chornobyl.”

(2) See, for example, Laurent Michelot, Tchernobyl. Visite post-apocalyptique, Paris, Le Chêne, 2020, pp. 44-46.

(3) See Amir Weiner, Making sense of war the Second World War and the fate of the Bolshevik Revolution, Princeton, N.J., Chichester, Princeton University Press, 2002.

(4) Alena V. Ledeneva (dir.), Russia’s Economy of Favours. Blat, Networking and Informal Exchange, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1998, p. 37.

(5) Anna Ivanova, « Magaziny ‘Beriozka’ : Paradoksy potreblenia v pozdnem SSSR », Moscou, Novoe Literatournoe Obozrenie, 2017.

(6) See, for example, the interview with Natalia Manzurova in the online magazine Mouvements, « De Maïak à Tchernobyl, la ‘guerre’ radioactive : une liquidatrice témoigne », 2016.

* Laurent Coumel is a lecturer at Inalco, researcher at the Centre de recherche Europes-Eurasie (CREE) at Inalco, and author of 24 heures de la vie à Tchernobyl (PUF, Paris, 2024, 195 p).

Link to the French version of the article

Translated from French by Assen SLIM (Blog)

To cite this article: Laurent COUMEL (2024), “Being young in 1986 in Pripyat, the satellite town of the Chernobyl nuclear power station,” Regard sur l’Est, 22 April.