The steep streets of Tbilisi turned blue and yellow. This sign of the Georgian population’s unwavering support for Ukraine in its fight against Russian aggression contrasts with the more ambiguous position of the Georgian government. The Russian invasion and the announcement of the partial mobilization had a particular resonance in this Caucasian country.

On 21 September 2022, Vladimir Putin announced the partial mobilization of Russian reservists to reinforce his troops in the war launched eight months earlier against Ukraine. This announcement prompted many Russians to leave the country by air, at sometimes exorbitant prices, or by land, to neighboring countries. Georgia was one of them: the Larsi border experienced unprecedented traffic jams, with peaks of more than 10,000 Russians crossing it daily to reach Georgia.

On 21 September 2022, Vladimir Putin announced the partial mobilization of Russian reservists to reinforce his troops in the war launched eight months earlier against Ukraine. This announcement prompted many Russians to leave the country by air, at sometimes exorbitant prices, or by land, to neighboring countries. Georgia was one of them: the Larsi border experienced unprecedented traffic jams, with peaks of more than 10,000 Russians crossing it daily to reach Georgia.

Since that, the number of Russians who have arrived in Georgia has been estimated at 100,000, although it is difficult to obtain reliable figures, and not all of them have stayed in the country. After the one in February 2022, this new wave of migration represents an additional challenge for Georgia, which has only 3.9 million inhabitants, shares a complex history with Russia, and has 20 percent of its territory currently occupied by Russia.

A bitter memory for Georgians

The current war echoes the two conflicts in Abkhazia in 1992 and South Ossetia in 2008, opposing, on the one hand, Georgians and, on the other, Abkhazian and Ossetian independence fighters, the latter supported by Russia. Following these conflicts, the two regions declared their independence from Georgia, which is still not recognized by the international community. Russian troops now occupy them. Going back further, Georgia was under the control of imperial Russia for almost two hundred years. Then, after a few years of independence, it was again under the power of the Soviet Union until 1991.

The Georgian population is still very critical of these years of occupation, particularly the Soviet period. This history feeds a perceptible fear in them and their solidarity with any people that Moscow threatens. If Georgian society was already not very Russian-friendly before the outbreak of the war, this feeling has become even more pronounced since February 2022.

From supporting Ukraine to an uprising against the Georgian government

These provisions thus led the Georgian population to help the Ukrainian people massively. As soon as Russia invaded Ukraine, emotions ran high in Tbilisi. For several days, demonstrations involving several thousand people were organized in front of the Parliament and on the capital’s main street, Rustaveli Avenue.

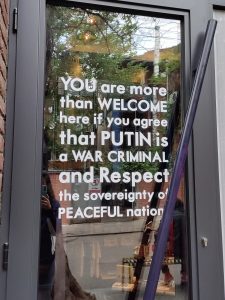

The city was also decked out in Ukrainian colors: flags abounded in the streets and on official buildings, appeals for donations multiplied, and shops, televisions, and mobile applications were mobilized. Many Georgians also volunteered to fight alongside Ukraine.

If the first demonstrations initially showed strong support for the Ukrainian people, they quickly turned into a wave of protests against the Georgian government, which was criticized for its position and considered too complacent towards Russia. On 1 March, the demonstration in support of Ukraine included for the first time an opposition leader, Elena Khostaria of the Droa party, who called for the resignation of Prime Minister Irakli Garibashvili. Most of the subsequent demonstrations will be organized by this party.

The ambiguous position of the Georgian government

The ambiguous position of the Georgian government

The government was initially criticized for not taking economic sanctions against Russia, while most Western countries were doing so. However, the Prime Minister justified himself: "Taking into account [its] national interests and [the] people’s interests, [Georgia] will not participate in financial and economic sanctions, as this will only cause great harm to the country and the people." Georgia partly depends on the Russian economy, which imports 94% of its wheat and exports over 50% of its wine.

In March 2022, the Georgian government agreed to open the Russian market to Georgian dairy products to benefit fifteen Georgian companies. Less than a month after the start of the war, this decision by Tbilisi caused outrage in Georgia and Ukraine. At the same time, several Georgian volunteer fighters wishing to go and fight alongside the Ukrainians had their planes blocked by the Georgian government because “this would mean a direct involvement of Georgia in the military conflict,” according to the leader of the ruling Georgian Dream party, Irakli Kobakhidze. Disappointed, the commander of this contingent of Georgian volunteers, Mamuka Mamulashivili, called the members of the Georgian government "Putin’s slaves.” This refusal of solidarity even led to the recall of the Ukrainian ambassador in Tbilisi by Volodymyr Zelensky.

Another area of political confrontation is the visa policy for Russians, which leads to some controversies in Georgia. While Russian citizens benefit from a visa regime considered by some to be very lax (they do not need a visa to enter Georgia, can stay there for a year, and return for a year after having made a return trip to a neighboring country), members of the opposition presented a bill in October aiming to tighten this visa policy. However, the ruling party refused this proposal and sent the United National Movement back to its responsibilities (in 2012, former President Mikheil Saakashvili had lifted visas for Russian citizens to contribute to improving relations with Russia).

Although the government has condemned the Russian aggression in Ukraine in practice, notably by voting for several UN resolutions, the Georgian Dream speech remains very reserved.

Divided authorities

The disorder is all the more significant because this cautious attitude of the Georgian government is far from being shared by the President, Salome Zurabishvili, who is much more critical of the Russian government. Since the outbreak of the war, tensions with Prime Minister Irakli Garibashvili have been exacerbated. It is known that, behind the head of government, the former Prime Minister and creator of the Georgian Dream, Bidzina Ivanishvili, partly shaped the government’s policy. The two men are considered, and constitutionally, the head of state has only a symbolic role. This influence has been criticized by the European Union, which has expressed “deep concern about Ivanishvili’s personal and business links with the Kremlin, which determine the position of the current Georgian government about sanctions against Russia.”

Georgian society is torn apart.

Georgian society is torn apart.

However, the biggest issue now is undoubtedly the fracture that is intensifying within Georgian society. The arrival of Russian deserters has had significant economic and social consequences (considerable rise in inflation and rents, inadequate public transport infrastructure, etc.). In addition to Ukrainian flags, graffiti calling for hatred against Russia, Vladimir Putin, and Russian citizens have flourished in Tbilisi. The debate is now omnipresent, and the tensions between Georgians and Russians are palpable. The result needs to be revised.

As legitimate as it may seem, given the country’s history and current geopolitical situation, the reluctance of some Georgians to tolerate the presence of Russian immigrants runs the risk of spreading dangerous xenophobia, which can also feed Moscow’s victim narrative. Some people in Georgia are well aware of this and advocate adopting a cautious and balanced integration policy.

Vignette and photos: © Clémence Béjot.

* Clémence Béjot is graduated from IRIS Sup’ in geopolitics and prospective and currently lives in Tbilisi, Georgia.

Link to the French version of the article

Translated from French by Clémence Béjot