In this exclusive interview with Regard sur l'Est, Armand de Saint-Sauveur talks about the creation of Intervalles and the reasons that led him to take a particular interest in Eastern Europe; the place is given to him by translators and the criteria that govern his choice of works to be published.

In this exclusive interview with Regard sur l'Est, Armand de Saint-Sauveur talks about the creation of Intervalles and the reasons that led him to take a particular interest in Eastern Europe; the place is given to him by translators and the criteria that govern his choice of works to be published.

and the criteria that govern his choice of works to be published.

Why did you create a publishing house? What is the specificity of Intervalles?

I created Éditions Intervalles in the mid-2000s. I lived a few years in Southeast Asia, traveled a lot, and found that French-language literature sometimes tended to have a very short horizon. I then felt like mixing cultures without preconceived ideas or bias.

Could you name some of your first published titles?

In the early years, a few books quickly stood out: In Search of Hassan, a multidimensional travelogue about Iran by American Terence Ward; or The End is My Beginning by Tiziano and Folco Terzani, a beautiful dialogue between a father sensing the end coming and his son tracing together a life of travel, engagement, and interculturality; I could also mention Raga Mala, the autobiography of the immense musician Ravi Shankar, who has done much to popularize Indian music in the West.

Les éditions Intervalles, rue bleue in Paris

What place does Central and Eastern European literature have in your catalog? Do you find specificity in it?

It quickly established itself as a singular and fertile space. Many excellent authors were not translated into French. However, the somewhat agitated recent history of this part of Europe and the multiple cultural and geopolitical questions that these upheavals never cease to agitate make for a particularly fascinating literary territory.

However, I don't believe that one can link the potential of a work to its nationality... On the other hand, I try not to spread myself too thin for coherence. Serbo-Croatian, Bulgarian, Slovak, Polish, and Greek are the most represented foreign languages in the Intervalles catalog, even Turkish, Estonian, and Russian.

As for the choice, a foreign publisher, an agent, or a translator must have presented me with a text or an author with enough enthusiasm and within the framework of a motivated and coherent approach to our catalog for me to be tempted. Or that a theme seems to be engaging in the special treatment that this or that author will propose. Finally, I always ask myself when I read a text or an excerpt from a translation: how will it be read in ten or fifteen years?

Could you give a concrete example of a text that illustrates your point?

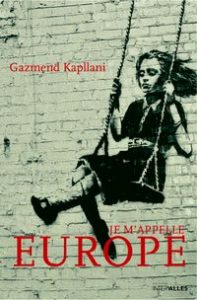

Yes: the work of the Greek-speaking Albanian writer Gazmend Kapllani is exemplary! On the surface, his first novel was a hybrid and somewhat unclassifiable text on sub-Balkan migrations, written by a quasi-stateless author and hunted down at the time by Greek neo-Nazis. As such, his text had not aroused much enthusiasm among French-speaking publishers. However, four books later, Kapllani has built a luminous and essential work on how great history and individual destinies are articulated in the Europe of the 20th and 21st centuries. He is now translated in many countries, although his texts often propose a complex construction (double narrative point of view, hybridization between fiction and non-fiction).

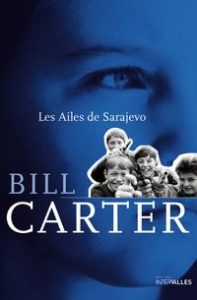

We could also mention The Wings of Sarajevo by Bill Carter, which is at the same time a great adventure novel, a travelogue, a war memoir, and a wonderful humanist tale of commitment to peace. It is a loving portrait of a country, Bosnia, written by someone who found himself immersed in it at the worst possible moment (the war of the mid-1990s) and who decided to do everything he could (in this case, to force the biggest rock band in the world to commit to peace) in order not to resign himself to the worst. In short, we again find many things in the same book: a writing, a commitment, a singular prism, and a mine of information on a country not always well known.

How do we identify contemporary authors in the region?

How do we identify contemporary authors in the region?

Publishing is a business of encounters. Publishers, agents, and translators are all people who pass on information. International fairs are an excellent place for exchange. Let's hope that they will resume soon because I believe more in embodied discussions than in telematic commerce.

The days of reading manuscripts at night in Frankfurt between meetings are long gone. Still, I remember dinners where publishers and agents of more than ten nationalities mingled in a joyful cacophony. I often think back, too, to the discovery of one of the few Anglo-Saxon authors in the catalog, Martin Millar, by his translator Marianne Groves: exhausted from never having succeeded in getting French-speaking publishers interested, she took the advice of a mutual friend and contacted me one day, explaining that she barely had the strength to talk to me about the author, so much so that she had exhausted herself in vain approaches to my colleagues for so many years. A week later, I called her back to tell her that I wanted to publish The Little Fairies of New York, which soon became an absolute bestseller and was quickly followed by three other titles by the same author, including the brilliant The Goddess of Daisies and Buttercups, which tells with fantasy and mischief the story of the staging of Aristophanes' Peace in the 5th century B.C...

Is Eastern European literature of interest to French readers?

Suppose the print runs are still often modest. In that case, we must point out that there has been a revival of interest from the French-speaking public in recent years, thanks to the work of new independent publishing houses that are doing a salutary job of clearing the way (Belleville Éditions, Éditions do, Agullo, Le Ver à Soie, etc.), as well as older, established houses that are continuing their patient and tireless work (Éditions Noir sur Blanc, Les Syrtes, etc.)

Is it difficult to find translators for Eastern European literature?

No, good translators exist. We can only hope that more publishers will be interested in these territories so that these translators will have more work! The translator is probably in the best position to evoke the singularity of this or that writing, and their experience is therefore essential. For example, in the "Sémaphores" collection, we systematically ask the translator to write an afterword to take the reader into the translator's workshop, which remains a place that is often secret and little-publicized. This results in personal, rich, and well-documented texts that put the translated work and its issues into a unique and fascinating perspective.

Is the digital transition affecting Intervalles? How have you adapted?

We have been somewhat pioneering in using social networks and have made a small half of the catalog available digitally, where relevant. We are making constant efforts to improve our referencing and imagine new communication and visibility strategies. As for the Eastern European works, most of them are published in print and digital format or about to be.

Moreover, we are distributed in France, Belgium, Switzerland, and digitally all over the world. We don't have a distributor in Canada at the moment. Still, we are looking into the possibility of printing some titles directly on the other side of the Atlantic so as not to deteriorate our carbon footprint should we decide to be regularly distributed there.

Consult the site of the Editions Intervalles.

* Assen SLIM is an economist, and professor at Inalco-Paris (Blog)

Link to the French version of the article

Translated from French by Assen SLIM