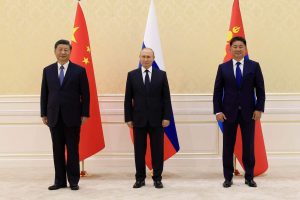

Presidents Vladimir Putin, Ukhnaagiin Khurelsukh, and Xi Jinping held talks on the sidelines of the 22nd meeting of the Council of Heads of State of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), of which China and Russia are members and Mongolia an observer. This trilateral exchange occurred in Samarkand and was not without ulterior motives.

Presidents Vladimir Putin, Ukhnaagiin Khurelsukh, and Xi Jinping held talks on the sidelines of the 22nd meeting of the Council of Heads of State of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), of which China and Russia are members and Mongolia an observer. This trilateral exchange occurred in Samarkand and was not without ulterior motives.

An asymmetric trilateral relationship inherited from history

Synonymous with wide open spaces and freedom, Mongolia has long been coveted by its two great neighbors, Russia to the north and China to the south. While the country was under Chinese-Manchu domination from 1611 to 1911, its Russian neighbor ensured that it counterbalanced the power of the Qing by establishing a diplomatic and commercial presence there. Russia also signed treaties with England and Japan at the beginning of the 20th century to delimit its zone of interest, which extended from Chinese Turkestan to Manchuria via Mongolia. It was a security imperative for Russia to have a buffer zone against China and Japan.

Russia also played a decisive role in Mongolia’s independence: Chinese troops were driven out of Mongolian territory with the help of the Russians, and the Mongolian authorities took advantage of the collapse of the Qing dynasty to move closer to Russia. Mongolia became a People’s Republic in 1924, and although it was never officially part of the USSR, it was often referred to as the Sixteenth Republic or a satellite country. For over twenty years, the Soviet Union was the only state to recognize Mongolia’s independence. Under Soviet pressure, China finally came around, and Ulaanbaatar gradually established diplomatic relations with other countries. The weakening of Russian positions in Mongolia began with the Mongolian democratic revolution of the winter of 1989/1990. It continued until December 1992, when the last detachment of Soviet soldiers crossed the Russian-Mongolian border. Since then, although ties have weakened, Moscow’s influence has been a significant factor in bilateral relations.

Today, Mongolia’s foreign policy is conditioned mainly by the implications of its geographic isolation. This situation is exacerbated by the significant power differential between Mongolia and its Russian and Chinese neighbors. Nuclear and demographic powers, permanent members of the UN Security Council, Russia, and China carry far more weight on the international scene than Mongolia, which, despite being three times the size of France, has a population of only 3 million. Therefore, Mongolia’s security strategy consists mainly of maintaining good neighborly relations with Moscow and Beijing and maintaining a ‘third neighbor’ policy. This concept, coined during the visit of US Secretary of State James Baker to Mongolia in 1991 and adopted as a foreign policy axis by the Parliament in 2011, consists of developing deeper relations with third countries to rebalance the weight of the two superpowers in the country. At the same time, Mongolia has been working since 2014 to institutionalize a trilateral dialogue format to ensure good neighborliness with its direct neighbors. The Mongolian president at the time, Tsakhiagiyn Elbegdorj (2009-2017), then proposed the establishment of the “Ulaanbaatar Meetings,” during which the three heads of state would meet to discuss infrastructure projects. Although the title was not retained, the principle has remained. Every year, the three countries’ leaders meet on the sidelines of the annual summit of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation.

Mongolia, a logistical hub for Russian and Chinese projects in Eurasia

By guaranteeing this regular exchange, Mongolia asserts itself as a transit space for the growing trade between its neighbors. Its objective is to promote the concept of steppe routes, which refers to the development of infrastructure projects, to position itself at the intersection of the Russian (Trans-Eurasian Belt Development) and Chinese (Belt and Road Initiative) connectivity projects. This ambition goes beyond the framework of trilateral cooperation since Mongolia, whose territory represents the fastest and most cost-effective route between Europe and Asia, is to use these projects to contribute to the development of overland trade between the two continents.

In 2016, Mongolia signed an agreement with its partners to create a China-Mongolia-Russia Economic Corridor based on 30 road and rail projects. The central road of the corridor runs from the Chinese port of Tianjin northwest via Beijing to the border crossing at Erenhot. The road then crosses Mongolia, enters Russia via the Trans-Siberian Express at Ulan Ude, and ends at Kuragino in Krasnoyarsk Krai. The road allows Mongolia to position itself as a logistical hub in a vast regional energy network known as the Northeast Asian Super Grid, which aims to take advantage of Mongolia’s vast energy resources, particularly useful for developing renewable energy in China, South Korea, and Japan. At their meeting in Samarkand on 15 September, the Russian, Mongolian, and Chinese leaders confirmed a five-year extension of the development plan for this economic corridor and officially launched a feasibility study on the modernization and development of the China-Mongolia-Russia railway. In addition, China may invite Russia and Mongolia to join the renminbi cross-border interbank payment system to simplify the settlement process and reduce the dollar exchange rate risk.

In this context, Mongolia has also been pleading for several years to construct a Russian-Chinese gas pipeline transiting through its territory, a project that Moscow and Beijing have long refused, seeing as a means of pressure for the Mongolian authorities. The first gas pipeline, Siberian strength, directly linking Yakutia to the far north-east of China, came into service at the end of 2019. It is all the more critical today as Europe turns away from Russia as a gas consumer, pushing the country to consolidate its energy presence in the East. In 2020, studies were launched to create Siberian Force 2, this time with the tube passing through Mongolia. Its construction should begin in 2024. This decision is a real turning point for Mongolia, whose economy is mainly based on livestock and agriculture.

Growing regional tensions

However, the development of cooperation between the three countries could be hampered in some ways. Mongolia did not find it necessary to use third-party advisors to assess the financial aspects of the pipeline-lining project, despite its lack of expertise in this area, and now fears that Moscow will transfer an unjustified share of the project’s cost to Mongolia, reserving an undue amount of profit for itself. The only way out would be for Mongolia to take out a large loan from Moscow, increasing its economic dependence and reducing its room for maneuver.

By establishing an asymmetrical relationship, Russia could claim to have an ally, even as it appears increasingly isolated internationally due to its war against Ukraine. The holding of the Vostok-2022 military exercises last September, under the supervision of the Russian President himself and in the presence of several allies, including China and Mongolia, testifies to what is at stake for Russia in these cooperative ventures, at least in terms of display.

Although Ulaanbaatar has adopted a neutral stance towards the war in Ukraine, Mongolian civil society and politicians such as former president Ts. Elbegdorj has publicly condemned Russia. This apparent contradiction attests to Mongolia’s difficulty positioning itself against its neighbor. Tensions were exacerbated when it became evident that, during the partial mobilization, the Russian authorities were disproportionately targeting ethnic minorities culturally close to Mongolia. It should be recalled that under the Qing dynasty and Tsarist Russia, Beijing and Moscow wrested two regions from Mongolia for administration: Inner Mongolia and Buryatia, mainly populated by Mongolian ethnic minorities. Despite Moscow’s lack of transparency about its losses at the front, it appears that regions such as Buryatia or Tuva suffered proportionately more casualties than the central regions of Russia. However, Ulaanbaatar did not comment on this disproportion. A discrepancy between the Mongolian authorities and the civilian population could also be observed in the policy of cultural assimilation of the inhabitants of Inner Mongolia launched in 2020 by China.

While Mongolia is bound to exercise skillful maneuvering towards Russia and China to ensure its security and development, the latter now have an equal interest in turning to the country as tensions between Beijing and Moscow on the one hand and the West on the other continue to grow. In this context, regional integration becomes an issue in itself. Moreover, in addition to its strategic geographical position, Mongolia can boast of being the country that maintains the closest diplomatic relations with North Korea; therefore, it appears as an even more valuable interlocutor in the eyes of its two significant neighbors.

Main sources:

- Munkhnaran Bayarlkhagva, “A New Russian Gas Pipeline Is a Bad Idea for Mongolia,” The Diplomat, 11 May 2022.

- Antoine Maire, La Mongolie contemporaine, Chronique politique économique et stratégique d’un pays nomade, CNRS Éditions, Paris, 2021, 348 p.

- David Teurtrie, “Vers un renouveau des relations russo-mongoles ?”, L’Observatoire, Centre d’analyse de la CCI France-Russie, 1 November 2018.

- Jargal, “Mongol, Oros, Hyatadiin turiin terguun nariin uulzaltiin talaar olon ulsiin hevleluuded” (The meeting of the Mongolian, Russian and Chinese leaders seen in the international press), Montsame, 16 September 2022.

- Elbegdorj, “Chingis Haan bol manai undesnii Baatar” (Genghis Khan est notre héros national), 24 Tsag, 12 January 2016.

- Bolor, “OHU BNHAU, Mongol zereg ulstai hamtarsan tsergiin surguulilt hiine” (Russia to conduct military exercises with countries such as China and Mongolia), mn, 30 August 2022.

Thumbnail: Presidents Vladimir Putin, Ukhnaagiin Khurelsukh, and Xi Jinping during their meeting in Samarkand on 15 September 2022 (Photo: Mongolian Foreign Ministry).

* Solen-Zaya Demars is an M2 student in International Relations at INALCO, specializing in studying Mongolia and the post-Soviet space.

Link to the French version of the article

Translated from French by Assen SLIM (Blog)