In the months following Russia’s large-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, Poland’s energy policy became an exercise in balancing priorities. To free itself from its dependence on Russian gas, Warsaw had to turn to a more expensive and polluting alternative: domestic coal. More than a political failure, this should be seen as a cold, pragmatic calculation imposed by the collision between geopolitics, economics, and climate ideals.

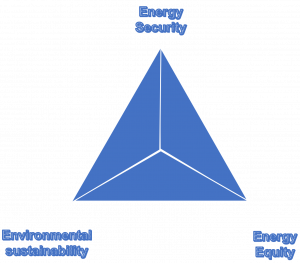

This collision can be understood through the “energy trilemma,” a constant and risky compromise between security (energy independence), equity (affordable prices), and sustainability (ecological transition). In most countries, one of these priorities dominates, to the detriment of the others. Before the shock of Russia’s large-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, equity was undoubtedly the main feature of Poland’s energy policy. Since then, Poland has been forced to shift its priorities to adopt a new, non-negotiable security-focused paradigm. To ensure its short-term economic survival, Warsaw has had to sacrifice its long-term climate goals temporarily.

This collision can be understood through the “energy trilemma,” a constant and risky compromise between security (energy independence), equity (affordable prices), and sustainability (ecological transition). In most countries, one of these priorities dominates, to the detriment of the others. Before the shock of Russia’s large-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, equity was undoubtedly the main feature of Poland’s energy policy. Since then, Poland has been forced to shift its priorities to adopt a new, non-negotiable security-focused paradigm. To ensure its short-term economic survival, Warsaw has had to sacrifice its long-term climate goals temporarily.

The “equity first” paradigm: the reality of pre-war Poland

Before 2022, Poland’s energy policy was based on its economic model, which was focused on exports and characterized by industrial power. To maintain the country’s competitiveness, Poland’s energy-intensive manufacturing sector therefore requires stable, low-cost access to energy resources. Through the lens of the Energy Trilemma, this would be defined by a firm reliance on energy equity, as energy affordability is paramount in an export-led, manufacturing-intensive society.

This economic reality has also shaped Poland’s approach to sustainability. Unlike the ‘balanced’ economies of Northern Europe, which drive growth through high-value services and domestic consumption rather than heavy industry, Poland cannot easily decouple growth from carbon. While Nordic nations primarily import energy-intensive manufactured goods (effectively outsourcing the pollution required to make them), Poland produces them. Consequently, the green transition has not been seen as an opportunity, but rather as a direct threat to this model of equity. The EU’s decarbonisation has led to higher costs in Poland than in other countries and to social upheaval. In fact, Poland’s historical opposition to the EU’s ambitious climate frameworks is rooted in the structural realities of its growth model, particularly its coal industry.

Russia’s illegal annexation of Crimea in 2014, for example, stimulated the integration, directly precipitating the adoption of the European Energy Security Strategy (May 2014) and the subsequent launch of the Energy Union framework (2015). Discussions within the European Council on climate and energy policy highlighted marked differences between, on the one hand, the northern European regions (including Germany), concerned about the environment and climate and advocating measures focused on sustainability, and, on the other, the Visegrad and Balkan countries, led by Poland, which are more dependent on fossil fuels; the latter prioritized security and, to that end, the use of these fuels(1). In essence, the energy security of northern countries has always been reconciled with sustainability objectives, while for central European and Balkan countries, this virtuous approach has proved more costly.

Nevertheless, integration has progressed thanks to compromise agreements. Concessions have been granted to certain Central and Eastern European countries, and the sanctions adopted against Russia since 2014 have avoided targeting energy.

At the same time, the previously set sustainability objectives have not been achieved. Certain compromise agreements have prioritized affordability over security and sustainability, even if this means exacerbating some countries’ energy dependence on Russia. Despite the Energy Union’s initial intentions for sustainable security, economic incentives such as declining domestic gas production in the EU, reliance on cheap Russian gas, and a lack of competition in liquefied natural gas (LNG) have weakened this policy. With no authority over national energy mixes, the EU has struggled to dissuade Member States from prioritizing energy imports from Russia. As a result, the EU’s dependence on Russian hydrocarbon imports (particularly gas) continued to grow between 2014 and 2022.

It should be noted, however, that Poland has not been purely obstructionist regarding sustainable development goals. Warsaw had its own, albeit slower, vision of a green future, detailed in its Energy Policy 2040 (PEP2040) and in its plans for large-scale offshore wind farms in the Baltic Sea. But for Warsaw, this transition had to take place on its own terms and timetable, including careful management of the decline of coal over several decades. Thus, Poland’s energy trilemma seemed clear until 2022: energy equity first, with a slow and cautious transition to sustainability. Energy security, in the form of vulnerability to Russian gas, was simply the price to pay for this model.

In 2022, security replaces equity as the new organizing principle

Russia’s large-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 was accompanied by what has become a fairly standard tactic for Russia: the use of energy as a weapon, with the cutting off of supplies via the Yamal gas pipeline (which crosses Belarus and Poland). For Warsaw, what had been an economic dependency suddenly became an existential security emergency. The central question of energy policy instantly changed from “What is cheapest?” to “What is not Russian?” The non-negotiable organizing principle of state policy became total independence from Moscow. Historically torn between economic cost imperatives and dependence on Russia, Poland was forced to give absolute priority to security.

This paradigm shift is profound. Independence from Russia has become both a strategic imperative and a moral duty. The question then facing Poland, as well as other European economies, was how to deal with this new situation: could countries use it as a final push towards sustainability, given that energy policy had already been completely overhauled, or would they instead seek cheap but carbon-intensive alternatives?

In this regard, Poland is a fascinating case: low-carbon technologies and diversification projects have suddenly been redefined as tools for national security rather than merely climate ambitions (2). The likelihood of a “carbon wall” separating Central and Eastern Europe from the rest of the world has diminished considerably, contrary to what researchers had predicted before Russia launched its war in 2022. The challenge was daunting: Poland had to replace Russian gas without delay, while its long-term green alternatives – notably nuclear and offshore wind power – would not be viable for at least a decade.

Why has sustainability been the short-term victim

Poland’s response was akin to an emergency operation, leading to the trilemma compromises being managed under extreme pressure. To save the economy, certain elements had to be sacrificed and, in the short term, sustainability unfortunately suffered.

Firstly, Warsaw has sought to strengthen its independence (security). The flagship Baltic Pipe project, which connects Poland to the Norwegian gas network, was accelerated and inaugurated in September 2022. This new lifeline, combined with increased LNG import capacity, is a statement of sovereignty. But it comes at a high cost: Norwegian gas and global LNG are much more expensive than the old Russian contracts.

This shift triggered the second crisis: that of fairness. With gas prices soaring worldwide, Polish households and industries faced a sharp economic downturn. The government was therefore forced to find a solution that would ensure both security and affordability. There was only one resource that could achieve this: domestic coal(3). To avoid power cuts and massive industrial failures, Warsaw turned to its most polluting resource. The government cancelled its plans to phase out coal and increased production. This response was widespread in Central and Eastern Europe and in Germany.

A new green patriotism

The war started by Russia has therefore forced Poland to take a significant step back from its short-term climate goals. This is not a return to the old paradigm of fairness above all else, but a tactical and temporary retreat aimed at stabilizing the situation.

Ironically, the shock has now created the political will for a green transition that was previously lacking. Projects once dismissed as costly “green idealism” are now seen as essential to national security. Warsaw’s ambitious plans for powerful nuclear reactors and massive investments in offshore wind capacity in the Baltic Sea are accompanied by a new narrative: it is not just about climate goals, but also about independence.

In the long term, the crisis, even though it forced Poland to burn more coal, may well have been the determining factor in the country’s eventual abandonment of this energy source. The new logic of “green patriotism” could prove more powerful than any European directive. Poland’s temporary setback in terms of sustainable development was a painful necessity. Still, it may well, in a cruel twist of history, have secured its long-term future, independent of Russia and, ultimately, more sustainable.

Notes:

(1) Knodt, M., & Ringel, M. (2022). European Union energy policy: A discourse perspective’. In M. Knodt & J. Kemmerzell, Handbook of Energy Governance in Europe.

(2) Gherasim, D.-P. (2023). The Europeanisation of the Energy Transition in Central and Eastern EU Countries: An Uphill Battle that Can Be Won, IFRI, Paris.

(3) Sgaravatti, G., Tagliapietra, S., & Trasi, C. (2022). National energy policy responses to the energy crisis. Bruegel.

Thumbnail: the triptych of environmental sustainability, energy security and energy equity (© Emil Schak Rønnow & Thanh Pham Xuan)

* Emil Schak Rønnow is completing a Master’s degree at ESSCA School of Management, following a degree in International Business and Politics from Copenhagen Business School.

** Thanh Pham Xuan is completing a Master’s degree at ESSCA School of Management, following a degree in Business Administration from Foreign Trade School.

Link to the French version of the article

To cite this article: Emil Schak Rønnow & Thanh Pham Xuan (2025), “Poland: the ‘energy trilemma’ born of Russia’s war,” Regard sur l’Est, December 29.