As Russia sinks ever deeper into its mortifying project, repression, and censorship, Sergey Parkhomenko, from exile, shares his observations on the current state of Russian civil society. Faced with omnipresent propaganda and increased repression, he outlines the challenges facing the opposition and analyses the impact of the war in Ukraine on domestic political dynamics.

In this second exclusive interview with Regard sur l’Est, exiled opponent Sergey Parkhomenko, creator of civic initiatives targeting journalistic and academic circles and the field of memory, discusses the current darkness in Putin’s Russia.

In this second exclusive interview with Regard sur l’Est, exiled opponent Sergey Parkhomenko, creator of civic initiatives targeting journalistic and academic circles and the field of memory, discusses the current darkness in Putin’s Russia.

Do you think civil society still exists in Russia despite the growing pressure of propaganda and repression?

Sergey Parkhomenko: It is becoming increasingly difficult to express opinions opposing the regime in Russia. Since 24 February 2022, total military censorship has been in place, with severe penalties for any criticism of the war in Ukraine or the Russian army or government. The Russian Criminal Code now imposes harsh penalties on anyone who opposes the regime. Moreover, the opposition is both banned and censored, resulting in hundreds of absurd trials and harsh prison sentences for those who dare to express an opinion contrary to the official doxa. Trials are multiplying, targeting journalists, activists, and local political figures. Demonstrations are brutally suppressed, making it challenging to assess genuine support for the opposition, although there is evidence of an active public for the independent press.

How is the population reacting to this repression? Is there still room for dissent in Russia?

It isn’t easy to estimate the true extent of dissent in Russia, but many citizens are informing themselves through independent channels such as YouTube, online media, and social networks. However, open demonstrations are rare, suggesting that repression has achieved its objective. Russia has developed a veritable “surveillance industry” with an omnipresent network of cameras, facial recognition systems, and total control of communications. It has become dangerous to express a point of view that disagrees with the official propaganda. State-controlled television, radio, and the press are forbidden territory for any expression that does not conform.

Although freedom of speech has been wiped out, civil society in Russia still manages to keep projects and initiatives alive. Citizens are actively informing themselves using independent media on the Internet, forming a community that exchanges information via social networks (Facebook, X, Telegram in particular). However, the absence of demonstrations or visible collective action bears witness to the fact that repression is weighing heavily on the population.

“Beware of CCTV,” St Petersburg (Credit: Céline Bayou).

Do you think time is on the Kremlin’s side in the conflict in Ukraine?

Time is an ally of the Kremlin as long as Russia has vast human resources to sacrifice. Despite the human cost, Putin, enjoying absolute power, seems prepared to continue the war. The method, which is ultimately relatively “primitive,” involves using the poverty of certain Russians to encourage them to take part in the war, thus creating a complex dynamic: the regime exploits the poverty of part of the population by using the war as an opportunity to escape from misery. Economic incentives, such as financial compensation for the families of deceased soldiers, become levers for recruiting individuals prepared to sell their lives. Putin’s regime recruits its soldiers more from medium-sized towns and the countryside than from big cities like Moscow, Petersburg, and Yekaterinburg. The regime does not even need to resort to patriotic hysteria to recruit. All it has to do is play on people’s misery by simply “buying” human life. This stark reality highlights the manipulation of the economic need to maintain a commitment to war.

A similar observation can be made about international sanctions, which have proved ineffective against the Putin regime’s economy. The economy continues to prosper despite external pressure. Key sectors such as gas, oil, and metals remain lucrative. The revenue generated seems sufficient to compensate for the loss of life, fuelling a war machine that draws on the misery of its citizens to maintain its momentum.

Sergey Parkhomenko

How can journalism raise the Russian population’s awareness of war?

Journalism plays a crucial role in revealing the realities of war, particularly by showing the price paid to keep Putin in power. By bringing people out of their lethargy, journalism seeks to raise awareness, particularly among those who live in poverty and are prepared to accept any opportunity that comes their way.

In a recent article, you raised the possibility of Vladimir Putin’s regime collapsing. Don’t you think that, beyond the president’s personality, the regime could persist or even grow stronger?

Human history has witnessed various totalitarian regimes, and historical experience shows that every regime, even totalitarian ones, is ultimately short-lived. After the death of a leader, there are often heirs, or even groups of heirs, who can temporarily strengthen and harden the regime. The advent of democratic mechanisms and the humanization of the state takes decades and generally follows a phase of increased repression and cruelty by the regimes in place. Russia, it seems, should not escape this historical rule.

Of course, the continued existence of this regime is closely linked to Vladimir Putin’s personality, who played a central role in its creation. Although his disappearance could have a significant impact, the regime seems unlikely to die out instantly. A transition to a more democratic and humane Russia would take time and not appear imminent.

You left Russia in April 2021, before the invasion of Ukraine by Russian forces. Do you think you can play a significant role, from the outside, in supporting Russian democracy?

I do my best to help support independent journalists, recognizing the influential, if constrained, power of their voices on the trajectory of Russia. As far as other civil society initiatives are concerned, I am fully committed. Since the beginning of the war, I have been actively involved in the Posledny Adres initiative, doing my utmost to guide it through this challenging period marked by virulent attacks. I aim to facilitate research under optimum conditions to illuminate the fate of many missing people. We continue to affix commemorative plaques to the fronts of houses, seeing them as increasingly precious testimonies when the value of human life seems to be declining.

At a time of war when Putin’s regime is minting human life, we, on the other hand, stress that every life is unique, invaluable, and deserves respect. My involvement in these projects is part of a wider anti-war and pacifist movement, which takes on particular significance in the current darkness in Russia.

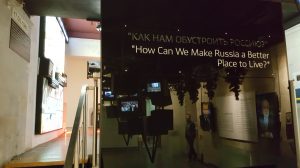

Museum of Russian Political History, St Petersburg (Credit: Céline Bayou 2019).

The Russian opposition in exile is often described as poorly organized and riven by disagreement. Do you think it can influence the course of political life in Russia?

Indeed, the opposition representatives are currently scattered, lacking any unifying and realistic projects understood as initiatives that could find an echo in Russia. A blatant example of this can be seen in the run-up to the presidential election in March 2024, where no credible opposition candidate is allowed to stand. All the candidates are closely linked to the Kremlin, thus destroying any chance of genuine competition [comments made before the emergence of Boris Nadejdine’s candidacy - Editor’s note].

The electoral situation in Russia has reached a point where voting has lost all meaning. The mechanisms for falsification are now unlimited, particularly with electronic voting imposed throughout the country. Coupled with non-existent monitoring, the absence of independent observers, and a press under the regime’s control, the Kremlin can declare the results as it sees fit. As a result, political debates are emptied of all substance. Even the vote “against all” loses its value. And the outcome of the 2024 election will be pure fiction created by the Kremlin.

For its part, the Russian opposition in exile is faced with a dilemma due to the absence of tangible and practical projects that could constitute concrete objectives in its struggle. This reality leads to sterile and despairing discussions, generating a particular form of trauma within the diaspora. When people realize that they have little control over Russian society, discouragement and even depression can set in.

Despite these challenges, the opposition in exile remains an alternative to the authoritarian regime in power. The voices of independent journalists, activists, artists, and other civil society actors in exile continue to be heard, helping to keep an alternative alive in the face of the regime’s lockdown at home. Investment in civil society projects remains the way forward for the Russian opposition in exile.

Thumbnail: Sergey Parkhomenko.

Read the first part of this interview.

Link to the French version of the article

* Assen Slim is an economist and professor of international economics (INALCO). Blog

To quote this article: Assen SLIM (2024), “Sergey Parkhomenko: the darkness of contemporary Russia,” Regard sur l’Est, 5 January.