The Kharkiv School of Photography, an anti-conformist, and experimental movement, was born in Ukraine in opposition to Soviet socialist realism. Thanks to this artistic movement, photography, seen mainly as a propaganda tool by the Soviet regime, acquired an absolute value of artistic and political protest.

Photographing in the Soviet Union

Photographing in the Soviet Union

In the Soviet Union, photography was subject to substantial state control. During the Stalinist period, photographers had to submit to the doctrine of socialist realism by representing a strong, happy, and proud USSR. This control was coupled with numerous visual prohibitions such as alcohol, smoking, disease, and nudity. Taking unauthorized photographs of strategic sites (bridges, industrial sites, railway stations, etc.) was also prohibited. These artistic diktats were relaxed somewhat under Khrushchev when he authorized the creation of amateur clubs in all Soviet republics. Although supervised and entirely focused on the technical aspect of photography, these clubs allowed amateur photographers’ first gatherings and exhibitions(1). Following the Prague Spring, censorship was again reinforced for two decades. It was in this context of renewed censorship that the Kharkiv School of Photography was born.

The waves of the Kharkiv school

The Kharkiv School is a movement that has evolved over more than 50 years of history, composed of three artistic waves and represented by about thirty actors(2). These successive waves have developed in parallel, allowing for critical inter-generational exchanges. The Kharkiv School can therefore be understood as a plural and varied artistic continuum whose members have created a distinct visual identity rich in innovative techniques and concepts.

In contrast to official imagery, its members offered a critical and ironic look at the Soviet environment, dealing with many taboo subjects such as disease, poverty, intimacy, nudity, and lack of infrastructure. Their photographs are also considered to be excellent testimonies of the urban development of Soviet Ukraine.

The Vremya Group

It isn’t easy to define the exact date of birth of the Kharkiv School of Photography. A crucial event in the establishment of this movement, however, was the unofficial creation of its first amateur group, Vremya(3): it was initiated in 1971 by two members of the Kharkiv regional photo club, Jury Rupin and Evgeniy Pavlov, who was joined by Oleksandr Sitnichenko, Anatoliy Makiyenko, Boris Mikhailov, Oleg Maliovany, Gennadiy Tubalev, and Oleksandr Suprun. Driven by their opposition to Soviet guns, they managed to get Vremya into working at the Kharkiv club in 1975. When the Soviet authorities became aware of their experiments, they quickly demanded that the club be closed down, thus condemning Vremya to operate in hiding.

The members of Vremya were opposed to the inertia of official photographs. One of the outcomes of this opposition was the ‘punching theory,’ according to which the picture should hit the viewer hard so that they question the nature of what is being presented. The group tried to show what was behind the official ideology by defying all prohibitions. Thus, the members of Vremya depicted food shortages, alcoholism, prostitution, suburban decay, and nudity. Because of their subject matter, these photographs were intended to be shared only in a restricted circle. The group had only one public retrospective exhibition in 1983, which was closed the same day by the authorities.

The most famous member of this group is the conceptual photographer Boris Mikhailov(4). His ironic treatment of everyday Soviet life contributed to the recognition of the Kharkiv school. He was responsible for the creation or promotion of many techniques and concepts that were taken up by his colleagues and, later, by his international peers. One of his best-known techniques is overlays (or sandwiches), which consist of superimposing color photos on top of positive ones. This technique, which allows for many extravagant creations, was used in particular by representatives of the Kharkiv school to accentuate the absurdity of the subjects treated. He is also at the origin of the artistic use of Louriki, a technique of coloring and manual modification of photographs. Finally, he is the father of lousy photography, consisting of the voluntary creation of defective black-and-white photos in opposition to the polished norms of Soviet art. An exhibition of almost 400 of his works is currently open until March 2023 at the Maison Européenne de la Photographie in Paris.

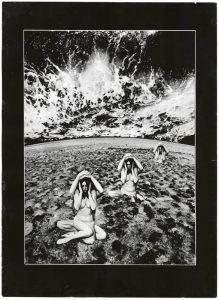

Another key player in Vremya, Oleg Maliovany, is also known for his prosperous technique, especially in coloring. He has created nudes amid alternative and apocalyptic worlds in a panoramic view, questioning the excesses of the technical progress glorified by the regime and exposing the fragility of humanity.

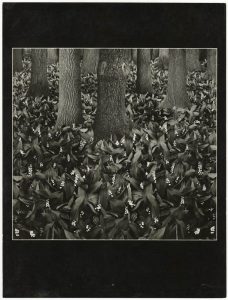

Finally, Oleksandr Suprun, whose work is characterized by photo collages with dramatic effects, can be mentioned. Using only his photographs taken secretly in the street, his compositions could take months to prepare. His best-known work is Lilies of the Valley (1975): using the same flower 51 times to create an ideal landscape with the Russian inscription “Children are the flowers of our life” this work is, in fact, a critique of the forced standardization of Soviet youth.

Spring in the forest. Lilies of the valley, Oleksandr Suprun, 1975, @MOKSOP.

The second generation

The second generation of the Kharkiv school, which emerged in the 1980s, was characterized by greater fluidity, with its members evolving in groups or operating in isolation. The most influential group of this generation, formed in aesthetic confrontation with Vremya even though it absorbed its influence, was Gosprom. Whereas Vremya's style was characterized by intense photographic retouching to accentuate the “punch” effect, Gosprom avoided in-depth retouching. Taking advantage of the context of perestroika, its members were able to come out of hiding and, in particular, to participate in public exhibitions, seminars, and festivals, allowing them greater exposure on a national and international scale.

Gazprom advocates an aesthetic that responds to the concept of “candid photography,” according to which the photograph should be taken without posing and without the consent of its subject to capture the actual reality. From a technical point of view, this response to new processes. For example, the members of Gosprom took black-and-white photographs with a closed aperture and point light to achieve more excellent sharpness and depth(5).

Untitled - M is for Metro, Misha Pedan, 1986, @MOKSOP.

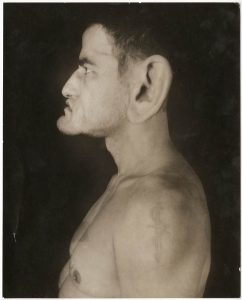

This wave was also made up of individual artists such as Sergiy Solonsky, whose work is characterized by a general rejection of color, photocollage, and an apparent lack of social criticism. Solonsky’s collages feature, among other things, mutant and deformed human bodies, a symbol of the general disarray in Ukraine at that time(6).

Untitled – Bestiary, Sergiy Solonsky, the mid-1990s, @MOKSOP.

Shilo

With the USSR's fall and many of its representatives exiled, the Kharkiv school fell into a 30-year slumber. The school's revival took place in the 2010s, with the creation of the group Shilo by Vladyslav Krasnoshchok, Sergiy Lebedynskyy, and Vadym Trykoz(7). Its composition has varied over time, but the group comprises Vladyslav Krasnoshchok and Sergiy Lebedynskyy. It gained significant media attention in 2012 with a remake of Mikhailov’s famous work Unfinished Dissertation, entitled Finished dissertation.

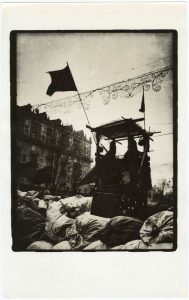

Despite the rupture of the USSR’s collapse, Shilo claims to be part of the two previous waves. He follows in the footsteps of Mikhailov and the Gosprom group while simultaneously creating his own visual identity. The photographs of these artists are often in black and white with more direct political messages than those of their predecessors. In their work, the group aims to expose the continuing effects of the Soviet legacy in the former Soviet republics through the prism of Kharkiv. Its members have addressed topics such as the condition of hospitals, poverty, and Euromaidan.

Untitled – Euromaidan, Sergiy Lebedynskyy, 2014, @MOKSOP.

A symbol of emancipation, anti-conformist, and experimental, the Kharkiv School of Photography has enabled a renewal of photographic practice in Soviet and post-Soviet Ukraine. While the first wave operated in clandestinity and sought to strike the viewer through complex processes, the second wave enjoyed greater freedom and wished to denounce reality as it was. The third wave, born after the fall of the Soviet Union, now sheds light on the persistent social legacy of the regime that its predecessors had denounced.

Intended to be exhibited in a museum scheduled to open in 2022 in Kharkiv, many of these photographs were forced into exile in Germany to escape Russian bombing and looting. More than ever, their fate echoes and recalls the dark hours of imperialism that seeks to rebuild itself.

Notes:

(1) Kharkiv regional photoclub, MOKSOP.

(2) Kharkiv School of Photography.

(3) Alina Sanduliak, “Igor Manko: We Tried to create works that would make you stop in front of them and think for a while,” MOKSOP, 26 August 2019.

(4) It is the subject of an exhibition until 15 January 2023 at the Maison Européenne de la Photographie in Paris (MEP).

(5) The Gosprom. Kharkiv School of Photography.

(6) Oleksandra Osadcha “Collage panopticon of Sergiy Solonsky”, MOKSOP, 6 March 2019.

(7) Nadiia Bernard-Kovalchuk, Lecture “The Kharkiv School of Photography: Deconstructing the Soviet Experience,” National Institute of Art History, 1 April 2022.

Photos: courtesy of MOKSOP.

Thumbnail: Gravitation, Gravitation, Oleg Maliovany, 1976. @MOKSOP.

* Tanguy Martignolles is a second-year student in the Erasmus Mundus Master’s program “Central & East European, Russian & Eurasian Studies” at the Universities of Glasgow and Tartu. This article was produced in collaboration with the Museum of Kharkiv School of Photography (MOKSOP).

Link to the French version of the article

Translated from French by Assen SLIM (Blog)