Interview with Régis Genté and Stéphane Siohan

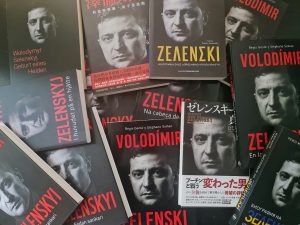

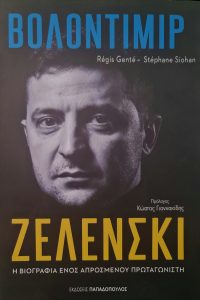

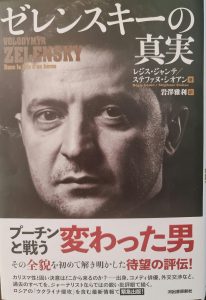

A few weeks after Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022, journalists Régis Genté and Stéphane Siohan, renowned specialists in Ukraine and Central and Eastern Europe, published the first full-length portrait in French of the Ukrainian president, Volodymyr Zelensky, Dans la tête d’un héros (Robert Laffont, May 2022).

In this book, which has since been translated into 13 languages and published in paperback in May 2023, the authors analyze how the former comic actor who became head of state almost by breaking in overnight became an undisputed warlord, both at home and with foreign powers. Nearly eighteen months on, what is our view of this great personality who defied the odds and went down in history?

In this book, which has since been translated into 13 languages and published in paperback in May 2023, the authors analyze how the former comic actor who became head of state almost by breaking in overnight became an undisputed warlord, both at home and with foreign powers. Nearly eighteen months on, what is our view of this great personality who defied the odds and went down in history?

Régis Genté and Stéphane Siohan were kind enough to answer Regard sur l’Est’s questions.

In your book, you recount the famous night of 24 February when, a few hours before Vladimir Putin launched his “special operation,” V. Zelensky addressed the Russians in their language (“We don’t need war. We will not attack, but we will defend. And you will see our faces. Not our backs, but our faces”). How do you explain this determination on the part of a President who had made peace his central campaign promise and whom you describe as having little interest in military matters?

S. S.: Although V. Zelensky can be considered a hero, he is not a hero in the sense of a Hollywood star or a media star. More profoundly, challenging to see in Western Europe, through his gesture of 24 February, he is taking up the torch of several personalities who have embodied an ideal of national emancipation, whether Poles or Russians, during Ukrainian history. Ivan Mazepa in the 18th century, Taras Shevchenko in the 19th century, and Simon Petlioura at the end of the First World War.

R. G.: There is undoubtedly the extraordinary moment that makes the man. But more than that, in my opinion, and this is the backbone of the book, there is a man who, in the democratic and relatively relaxed mood of a country in the throes of change, cannot but accompany the movement of the people to whom he belongs. In this sense, our book is very cautious about the notion of ‘hero’: he is indeed a ‘servant of the people,’ a reference to the title of the television series in which he played, from 2015, an ordinary man who became president of his country by accident and who fights against the powerful who have confiscated power, namely the oligarchs. This is not to be naive, as V. Zelensky’s relationship with the oligarchs is far more complex than what he says as an actor. But, all the same, in Ukraine, as we have known since the fall of Yanukovych at the beginning of 2014, a Ukrainian president can no longer make essential decisions against his people.

R. G.: There is undoubtedly the extraordinary moment that makes the man. But more than that, in my opinion, and this is the backbone of the book, there is a man who, in the democratic and relatively relaxed mood of a country in the throes of change, cannot but accompany the movement of the people to whom he belongs. In this sense, our book is very cautious about the notion of ‘hero’: he is indeed a ‘servant of the people,’ a reference to the title of the television series in which he played, from 2015, an ordinary man who became president of his country by accident and who fights against the powerful who have confiscated power, namely the oligarchs. This is not to be naive, as V. Zelensky’s relationship with the oligarchs is far more complex than what he says as an actor. But, all the same, in Ukraine, as we have known since the fall of Yanukovych at the beginning of 2014, a Ukrainian president can no longer make essential decisions against his people.

Can you define what you mean by ‘Zelenskism’ and how it is revealed in the light of these dramatic events? How did V. Zelensky change his image from that of “Captain Obvious” to that of a professional communicator during a war?

R. G.: The Zelensky of today is not the Zelensky of 24 February 2022. Before the large-scale invasion of Ukraine, it was a mixture of political sense and good feelings that were not necessarily translated into reality, of communication in the guise of politics, of populism whose virtue was to please the people and follow them. Communication was at the heart of this political project. It remains so, and we can see how important this aspect remains, even if there are failures. But, with the war, we can also see how much this communication is based on a real fight, a constancy in determining the country’s priorities.

S. S.: Today, the communicational dimension of “Zelenskism,” if it exists, is still present. But it is established much more in a personal incarnation of power. V. Zelensky proved that he was the right man for the job; there is a “republican” dimension to the providential man in the sense of the historical political tradition of these lands located between Ukraine, Poland, and Lithuania: power incarnate, but highly decentralized, based on horizontal and anti-authoritarian logics. V. Zelensky - and this was unexpected - embodies the figure of the hetman, the Cossack warlord, who is both powerful and respected, but who can be dismissed by his troops and his people if he fails to meet the expectations of the rank and file.

S. S.: Today, the communicational dimension of “Zelenskism,” if it exists, is still present. But it is established much more in a personal incarnation of power. V. Zelensky proved that he was the right man for the job; there is a “republican” dimension to the providential man in the sense of the historical political tradition of these lands located between Ukraine, Poland, and Lithuania: power incarnate, but highly decentralized, based on horizontal and anti-authoritarian logics. V. Zelensky - and this was unexpected - embodies the figure of the hetman, the Cossack warlord, who is both powerful and respected, but who can be dismissed by his troops and his people if he fails to meet the expectations of the rank and file.

We know that V. Zelensky owes much of his political rise to oligarchs. What role are they currently playing, and could they be helpful to a post-war Ukraine?

S. S.: The Ukraine of 2023 is no longer the Ukraine of 2021. The war has hit the industrial areas of eastern and southern Ukraine hard: Mariupol, Zaporijia, Dnipro, Odesa... The oligarchs have seen their assets destroyed or confiscated. Their wealth has melted away. An Akhmetov no longer has the same aura, and a Kolomoïsky is nowhere to be seen. Dramatically, Ukrainians are once again in control of their destiny. V. Zelensky knows full well that from now on, he has the upper hand over the oligarchs, whatever the war’s outcome.

R. G.: V. Zelensky owes a great deal to an oligarch, Ihor Kolomoïsky. And the sequence that began with Zelensky’s election in May 2019 on the eve of the war shows how dependent he was on him. However, the President has gradually had to cut his ties, primarily because he was forced to do so by international financial backers. With the other oligarchs, you get the impression that there were negotiations after V. Zelensky arrived at Bankova. Then, in 2021, V. Zelensky had a highly dubious anti-oligarch law passed because of the vagueness of the definition of an oligarch. It reduced their power, for example, by depriving Rinat Akhmetov of his media group.

We don’t see much of the oligarchs in this war, and they don’t communicate much, even though they seem to contribute to the war effort. The only absolute oligarchy in the former Soviet space before 2022, characterized by the importance of the Firtach, Akhmetov, Kolomoïsky and other Pintchouk, who had their group of deputies, media, affianced in the senior administration and who almost all cultivated relations with Russia, constituting Moscow’s main lever of influence in the country, Ukraine will never be the same again in this respect. After Boutcha, Marioupol, Izyoum... this influence will be difficult to envisage.

You say that V. Zelensky and his team believed that the Ministry of Defence should be entrusted to civilians with a good management profile rather than senior officers trained during the Soviet era. What impact has this initiative had on military operations?

You say that V. Zelensky and his team believed that the Ministry of Defence should be entrusted to civilians with a good management profile rather than senior officers trained during the Soviet era. What impact has this initiative had on military operations?

S. S.: The great leaders of the Ukrainian army, General Valery Zaloujny, Commander-in-Chief of the Ukrainian Armed Forces, and Colonel General Oleksandr Sirsky, who directs operations in the east of the country, were trained during the Soviet period. They know their enemy’s mentality inside out. But the army of 2023 has nothing in common with that of 2014, at the start of the war in the Donbas. The difference lies in the officers and non-commissioned officers. The latter have synthesized three cultures: the experience of fire during the war in the Donbas, the integration of the decentralized spirit of the volunteer battalions, and the training, over the last ten years, of officers from the American, Canadian, British, and Baltic armies. Thousands of soldiers and officers have passed these training courses, which have helped to develop the decision-making autonomy of the intermediate echelons - the non-commissioned officers - in a spirit of individual responsibility. This Copernican change in military culture is undoubtedly even more potent than the appointment of this or that minister of defense.

Let’s assume that Ukraine wins: how do you see V. Zelensky’s future in this post-war Ukraine, which will have to rebuild itself, maintain national unity, and speed up reforms?

R. G.: I am far from certain that Ukraine will emerge victorious from this war. What you can sense is the determination on the Ukrainian side. This means that now is not the time for polemics. For example, will V. Zelensky not be criticized by officers once the war is won? That has been said. Won’t he be made to pay for his mistakes, starting with his unwillingness to believe in Putin’s decision until 23 February 2022? I feel he will hold out and could be the one to keep the presidency after the victory. But with what power? His power before February 2022 was relatively weak, namely that of the head of a state where the democratic mood is such that he cannot decide the essentials on his own.

S. S.: As long as Ukraine is at war, there will be no elections so that V. Zelensky will remain President. Unless the country collapses, which is impossible to foresee at the moment, but if he wins the war, his popularity will be such that he will undoubtedly be able to remain, President if he feels like it. No political force seems able to offer an alternative, even if some personalities are emerging on the edge between civil society and the military effort.

In the event of a reverse scenario, do you think V. Zelensky would be inclined to commit to territorial concessions to end Russian aggression? Do you think a “frozen” conflict is plausible?

In the event of a reverse scenario, do you think V. Zelensky would be inclined to commit to territorial concessions to end Russian aggression? Do you think a “frozen” conflict is plausible?

S. G.: In an interview with Russian opposition journalists at the end of March 2022, he was asked this question: he replied that it would not be up to him to decide, that the decision would be collective, that of a people. About Crimea, he mentioned the idea of a referendum to decide whether or not to concede it to Russia. And here’s where the comedian comes in: let’s hold this consultation after a specific time, say in 2036... the year when V. Putin will, in theory, no longer be able to stand for re-election. I firmly believe that he can take such a decision and make territorial concessions, but not without securing national consensus.

R. G.: A political iron law has been in place since the late spring of 2022: Ukraine must regain its sovereignty within its 1991 borders, including the Donbas and Crimea. No one in Ukraine would dare oppose this hypothesis. Nevertheless, behind the scenes, and even within the People’s Servant political current, some voices believe that if Ukraine manages to regain control over the territories it controlled before 24 February 2022, i.e., without the so-called People’s Republics of Donetsk and Luhansk as well as Crimea, this would already be a victory and negotiations could begin with a weakened Russia. But the longer the war continues, the more Ukrainian opinion - and not the leaders - becomes maximalist.

You write that if Ukraine survives this war, the “denazification” operation launched by V. Putin will be the tomb of the Kremlin’s future ambitions in this territory. Does this mean, as many Ukrainians believe, that this war can only end with the collapse of Russia?

S. S.: The Ukrainians, and here I’m not talking about V. Zelensky, take a completely different view. For many, victory for Ukraine will only come through the collapse of the Russian Federation in its current form.

R. G.: One gets the impression that, if this is not the case, at least as far as the collapse of imperialist Russia is concerned, this war will resume sooner or later. Just as it resumed, in 2022, after marking a kind of pause after the Minsk II agreements (2015). Without talking about the collapse of Russia, which could be defined in a thousand ways, I would say that this war can only end if Russia loses. This probably means restoring Ukraine’s territorial integrity, including Crimea. Crimea is crucial; its return to Ukraine would mean the death of Putin’s Ukrainian project far more than the Donbas. But it’s undoubtedly a red line for him, possibly justifying the use of tactical nuclear weapons. If Crimea were taken back by Kyiv, V. Putin could fall. But he could fall without Russia collapsing, which would then be led by the regime’s caciques, who would explain that they were against the war but could not oppose it.

Photos: © Régis Genté.

Link to the French version of the article

Translated from French by Assen SLIM (Blog)