Adored or hated, Soviet architecture is one of the vital components of the urbanism of Vilnius, the capital of Lithuania. Suppose the question of its preservation has long been posed at the individual level. In that case, the debate on a national and media scale is a more recent phenomenon, which deserves to be understood under the economic, political, and memorial prisms.

The architecture of a city, far from being neutral, is an ideological and identity message. It informs us how its actors want to represent and identify themselves. Like all Soviet republics, Lithuania has been deeply marked by the urbanistic and architectural changes of the 20th century. Today, if the Soviet ideology has disappeared, its architecture remains. Neglected by the national debate for decades, its presence nevertheless raises questions: does this heritage have a place in the capital, and if so, which one? Through two case studies, the Sports Palace and the arrival station of the Vilnius airport, we can see that the Soviet architectural heritage remains subject to economic and identity-related pressures that can question its existence.

Soviet Architecture in Lithuania

The Soviet power considered urban planning and architecture essential to establishing the communist ideal. Upon their arrival in Vilnius, the Soviets first sought to depersonalize the established urbanism(1) by renaming public places and removing symbols deemed parasitic from the main buildings before bringing in new buildings, few in number, in Stalinist style. But it is the arrival to power of Nikita Khrushchev and, with him, the advent of mass housing and modernism which will cause the fundamental transformation of Vilnius: many blocks of housing and official buildings of modernist style remain today in the city center.

After regaining its independence in 1991, Lithuania de-Sovietized but did not opt for the massive destruction of these Soviet buildings, the economic transition limited the budgets allocated to urban renewal, and due to lack of funds, the vast majority of Soviet buildings were rehabilitated. A symbolic example of this process is the recovery of the structure of the Supreme Soviet of the Socialist Republic of Lithuania for the benefit of the national parliament, the Seimas.

La Seimas (May 5, 2021).

Plural memories and economic interests: the Sporto Rūmai

If the Seimas shelter is not questioned today, other Soviet buildings are. This is notably the case of the Sports Palace, located in the center of the city: a brutalist building designed by the young Lithuanian architect Henrik Karvelis, it was inaugurated in 1971. Its imposing structure and cable-stayed roof, unique in Lithuania, make it an object of artistic interest.

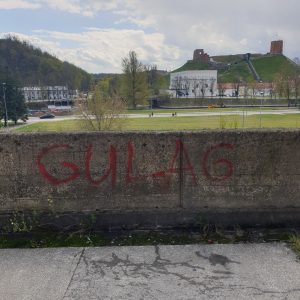

Damaged and tagged front facade of the Sporto Rūmai.

Damaged and tagged front facade of the Sporto Rūmai.

Back of the building, revealing its impressive cable-stayed roof (April 2, 2021).

Designed to host sporting and cultural events, this building is nevertheless an object of memory and controversy. In addition to its obvious link with Soviet ideology, it is also subject to debate because of its location since it was built on a former Jewish cemetery, active from the 16th to the 19th centuries, and destroyed by the Soviets in 1952. The building was used for some time after the recovery of independence and then gradually abandoned. It was definitively closed in 2004, but this did not prevent it from being listed as a national heritage site in 2006.

Tag on the Sporto Rūmai testifying to its historical and emotional charge (May 5, 2021).

In 2015, the building was bought by the Turto Bank(2), which decided to transform it into a conference center, a building that the capital was then sorely lacking. However, the project was delayed due to a lack of funds, the cancellation of tenders, widespread mistrust, and the Jewish community's request that the space becomes a place of remembrance. A compromise was finally found in 2021, imagining the conversion of the building into a conference center and the development of the surrounding space into a memorial. Unfortunately, in the same year, the Turto bank and the government decided that the increase in the price of the renovations made it no longer a profitable investment.

In January 2022, a project in favor of Jewish memory appeared again under Prime Minister Ingrida Šimonytė, who proposed to transform the building into a museum of Lithuanian Jewish memory, modeled on the Museum of the History of Polish Jews in Warsaw(3). This is, at this stage, a simple proposal. Pending a final project, the building itself remains abandoned. Although, in theory, the Turto Bank is responsible for its upkeep, the reality is more complicated: the Sports Palace, located in the center of the city, has been tagged and squatted and has deteriorated considerably. Ultimately, it appears to the citizens as a neglected specter of Soviet times.

A new national debate: the Vilnius airport arrival station

The gateway to Lithuania for most international travelers, this building suddenly became an object of controversy in 2021, under the impetus of the Minister of Transport, Marius Skuodis(4).

Facade of the Vilnius airport arrival station (May 10, 2021).

Soviet statues on the facade of the building (May 10, 2021).

Built-in 1954, this building is one of the few preserved examples of classic Soviet airports. Because of its artistic value, it has been listed as a Lithuanian heritage site since 1993; an act intended to protect it from destruction. If its interior has been refurbished, its facade is still decorated with Soviet statues. This façade now questions the legitimacy of the building about existence in its entirety. Suppose Mr. Skuodis put forward an economic argument, denouncing the high cost of maintaining the facility. In that case, it is the idea of identity that was put forward: for the minister, the building should be destroyed because it does not correspond “to the image of Lithuania.” The point here is to dissociate the image of Lithuania from the Soviet imaginary at the end of a process of differentiation and rejection: the minister denies the Soviet heritage as constitutive of the modern identity of Lithuania.

The announcement of the demolition project was then picked up by the media, sparking a nationwide debate. Shortly after this statement, the National Heritage Commission decided to pronounce itself and declared that the national heritage status of the building excluded any demolition project. In theory, this argument should have been enough to end the debate. Except that in 2016 the same Commission withdrew the same legal protection from Soviet statues then under renovation, proving that the legal protection of heritage can be revocable.

The controversy has become even more intense in the context of the war in Ukraine, with the head of communications for Lithuanian airports, Marius Zelenius, accusing the building of being a tool of Russian soft power, contributing to the division of society. This is a rhetoric of securitization: the structure is not only defined as non-representative of the Lithuanian identity but as a threat to it. Destroying it would therefore help to protect it.

But another camp has been formed: Vytautas Juozapaitis, director of the Parliamentary Committee on Culture, defends the building in the name of its educational value. Preserving it is a reminder of Lithuania's dark times, rhetoric that also uses differentiation, but this time as protection. In this logic, the building is not a threat to Lithuanian identity but rather a means of strengthening it. The building becomes a negative definition of Lithuanian identity, reminding us what it is not.

If the destiny of Sporto Rūmai depends on both economic and memorial considerations, that of the Vilnius air terminal has more to do with elements of identity; initially approached from an economic angle, the question of preserving this building quickly became a media debate around educational, identity and even geopolitical issues.

Soviet architecture, although recognized as part of the national heritage, remains an object of questioning in Lithuania. Whether it provokes admiration, nostalgia, horror, or anxiety, it remains, in any case, a strong emotional charge.

Notes:

(1) Theodore R. Weeks, “Remembering and Forgetting: Creating a Soviet Lithuanian Capital. Vilnius 1944–1949”, Journal of Baltic Studies, 2008, pp. 517-533.

(2) Paulius Viluckas, “Vyriausybė atsisako Vilniaus kongresų centro projekto, ieškos alternatyvų” (Government rejects Vilnius Congress Center project and will seek alternatives), Delfi.lt, August 16, 2021.

(3) “Vilnius Sports Palace could be turned into a Jewish museum, Lithuanian PM suggests,” LRT.lt, January 27, 2022

.(4) Jonas Deveikis, “Lithuanian Airports says Soviet-era terminal 'a propaganda tool', calls for demolition,” LRT.lt, April 23, 2022.

Photos: © Tanguy Martignolles.

* Tanguy Martignolles is a second-year student in the Erasmus Mundus Master's program "Central & East European, Russian & Eurasian Studies" at the universities of Glasgow and Tartu.

Link to the French version of the article

Translated from French by Assen SLIM (Blog)