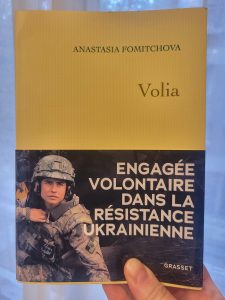

Anastasia Fomitchova is the author of the highly acclaimed Volia. This young Franco-Ukrainian doctor of political science, who had no prior connection to war, recounts her experience as a combat nurse on the front lines. Now committed to supporting Ukraine’s accession to the EU, she reflects on the incredible resilience of Ukrainian society, the imperfect support of Western allies, and the progress of reforms in wartime.

This was not the first such experience for Franco-Ukrainian researcher Anastasia Fomitchova: in 2017, at the age of 23, she had already chosen to join the Donbass as a combat nurse, responsible for first aid. Immediately after 24 February 2022 and Russia’s large-scale invasion of Ukraine, she suspended her PhD. She decided to return to her native Ukraine as a medic, participating in the defence of Kyiv, the eastern front, and the Kherson counter-offensive. In her recently published book, she recounts this experience, combining personal accounts with reflections on Ukrainian resilience, or Volia, which she defines as “the strength nourished by the love we have for our country and our freedom,” in the face of a Russia that continues to question the foundations of its own identity.

This was not the first such experience for Franco-Ukrainian researcher Anastasia Fomitchova: in 2017, at the age of 23, she had already chosen to join the Donbass as a combat nurse, responsible for first aid. Immediately after 24 February 2022 and Russia’s large-scale invasion of Ukraine, she suspended her PhD. She decided to return to her native Ukraine as a medic, participating in the defence of Kyiv, the eastern front, and the Kherson counter-offensive. In her recently published book, she recounts this experience, combining personal accounts with reflections on Ukrainian resilience, or Volia, which she defines as “the strength nourished by the love we have for our country and our freedom,” in the face of a Russia that continues to question the foundations of its own identity.

Anastasia Fomitchova kindly agreed to answer questions from Regard sur l’Est.

In your book, you recount your successive commitments between 2017 and 2022, the rupture this personal choice entailed, the fear you may have felt, and the need to go to the front line... How do you assess Ukrainian society’s ability to hold out in the long term, given that Russia is deliberately waging a war of attrition?

Anastasia Fomitchova: To fully understand Ukrainian society’s capacity to hold out in the long term, we must go back to the roots of the armed mobilisation in 2014. After the fall of Viktor Yanukovych’s regime, in a context marked by two decades of budget cuts, the sale of arms stocks on Ukrainian soil, and an apparent lack of willingness on the part of the political and economic elites to invest in the defence sector, it was ordinary citizens who took charge of organising it. In 2022, as in 2014, civil society joined the ranks of the army. Resistance to the invasion, therefore, relies above all on these powerful social ties between the military and society.

It should be remembered that the war is very costly for Ukrainian society, which is about to enter its fourth winter of war and, in February 2026, its fifth year of total conflict. Every Ukrainian family has at least one relative who has joined the army, been wounded, or killed on the front line, or in a bombing raid behind the lines. This creates a firm moral commitment to refuse to give in to Russian aggression. Russia targets energy infrastructure as a priority and does not hesitate to target other civilian infrastructure – schools, supermarkets, hospitals, churches – in complete violation of international humanitarian law, with the aim of “breaking the morale” of the population and undermining the war effort. But this strategy of terror is having the opposite effect. Ukrainian society has developed remarkable resilience: public services are functioning, engineers are repairing the damage caused by night-time strikes, and municipalities have set up “invincibility points” where people can heat themselves and recharge their electronic devices during power cuts. Thus, from the point of view of civil society, continuing to live in cities despite massive attacks and water and electricity cuts, and keeping the economy running, is a form of resistance to Russia’s desire to destroy the country.

From a military perspective, the situation is no longer the same as it was in 2022. The development of the defence sector – Ukraine now has the capacity to produce large quantities of drones and its own long-range missiles to strike military targets in Russia, such as logistics centres, weapons depots and refineries supplying the Russian armed forces – has helped to rebalance the balance of power on the ground. It should be remembered that, since 2022, the Russian army has advanced only about 1% into Ukrainian territory, compared to the areas conquered before and during 2022. Thus, both on the front lines and behind them, Ukrainians have developed the capacity to withstand Russian aggression not only from a military standpoint but also through social and moral cohesion. In a context where Russia is banking on attrition, Ukrainian society continues to resist to ensure the existence of the Ukrainian state.

Anastasia Fomitchova (© JF PAGA).

In your book, you denounce the discrepancy between the procrastination of Ukraine’s allies and the urgency of the situation on the ground: beyond the daily issue of arms deliveries, what leverage do you think European countries have today to force Vladimir Putin to enter into sincere negotiations?

The timing of European countries' decision-making does not align with the war on the ground. By refusing to react in 2014 and setting red lines, Europe has placed itself in a position of weakness. From 2022 onwards, the reluctance to supply arms reflected a lack of political will, giving Russia a strategic advantage over European countries, which, for fear of escalation, had long limited themselves to supplying defensive weapons. This excessive caution, which Moscow fully understood and exploited, allowed it to continue its offensives.

Since 2014, and even more so since 2022, Western countries have refused to engage in confrontation with Russia due to its blackmail regarding the use of nuclear weapons. Already in 2014, Vladimir Putin declared himself ready to use nuclear weapons in the event of Western intervention during Russian operations in Crimea. In 2015, the Minsk agreements froze the conflict in eastern Ukraine but did not address the peninsula’s reintegration. This refusal to take any position other than a policy of compromise towards Moscow paved the way for the large-scale invasion of February 2022.

It is nevertheless essential to recall that Russia understands only the balance of power. Despite political initiatives, the issue of sending troops to Ukraine remains, even today, a source of disagreement among Ukraine’s allied countries. In the absence of direct engagement on the ground, apart from the promise of deploying reassurance troops envisaged following a ceasefire, Western countries nevertheless already possess concrete levers: immediately strengthening the air defence of Ukrainian cities; relaunching the production and delivery of strategic weapons, in particular long-range missiles; investing massively in Ukraine’s defence sector; improving the implementation, monitoring and coordination of sanctions targeting key sectors of the Russian economy. Another decisive lever concerns the seizure of frozen Russian assets as collateral for a reparations loan, which could be used to enhance the Ukrainian army’s defensive capabilities while sending a strong signal to Moscow. It must be noted that today, Russia still refuses a ceasefire, and that it is, above all, targeted strikes on Russian territory that make it possible to rebalance the military situation on the ground. In other words, there is no other way to compel Vladimir Putin to engage in a genuine negotiation process than by intensifying economic pressure on Russia and placing Ukraine in a position of military strength. Apart from prisoner exchange agreements, no diplomatic effort launched since January 2025 has succeeded.

You write that this war will allow Ukraine to break free from old patterns of corruption and lay the foundations for a new era. But you also mention the demographic losses since 2014 and the fact that Ukraine has lost its “brightest elements on the front line.” How do you see the future of this battered country? You now live in Kyiv and are involved in projects related to Ukraine’s integration into the European Union. What European future do you envisage for Ukraine, and on what timeframe?

While it remains challenging to project oneself on the question of accession, since this is also linked to the EU’s ability to overcome its internal blockages, Ukraine’s entry into this process has unquestionably accelerated the implementation of specific reforms. In June 2022, the granting of EU candidate country status led the European Commission to define a set of prerequisites for opening negotiations. These recommendations focused in particular on a profound reform of the judicial system, the strengthening of the fight against corruption, especially at the highest level, the “de-oligarchisation” of the system, and the adaptation of legislative frameworks to European standards in the areas of combating money laundering, media regulation, and the protection of national minorities.

Several notable advances should be highlighted in this respect. At the legislative level, Ukraine took a significant step forward in September 2025 by completing the assessment of the conformity of its legislation with European standards, which began in July 2024 as part of the accession negotiations. In the field of anti-corruption, the full-scale war and pressure from Western partners have enabled the relaunch of specific reforms that had stalled since 2019 and limited oligarchs' influence on the political scene.

Indeed, since the mid-1990s, Ukraine has been suffering from systemic corruption fuelled by a deeply entrenched oligarchic system, with business people using institutions to protect and expand their economic capital. Before 2022, many reforms were thus blocked by political actors acting in the service of their private interests. In the context of the full-scale war, alongside the strengthening of institutions, the political authorities have launched a vast campaign of “de-oligarchisation,” profoundly altering the balance of power with these economic actors. Some have been arrested, others have left the country, and all have seen their economic capital significantly reduced, notably due to the destruction or loss of control over numerous industrial infrastructures.

Finally, beyond the pressure exerted by Western partners, it is essential to highlight the central role of civil society in these developments. Last summer, an attempt by the executive power to restrict the independence of two key institutions, the National Anti-Corruption Bureau (NABU) and the Anti-Corruption Prosecutor’s Office (SAPO), triggered a strong reaction from civil society, which led the authorities to reverse their decision. This mobilisation illustrated the central role that civil society continues to play, alongside international actors, in pursuing and consolidating reforms linked to the European integration process. In sum, despite the context of war and attempts at obstruction, Ukraine has managed to maintain a dynamic of institutional transformation within the framework of European integration. The success of this endeavour, therefore, now rests on maintaining a balance among political will, international pressure, and civil society’s capacity to ensure respect for the independence and integrity of institutions.

Link to the French version of the article

Translated from French by Assen SLIM (Blog)

To cite this article: Céline BAYOU (2025), “Ukraine: ‘It is essential to recall that Russia understands only the balance of power’ – Interview with Anastasia Fomitchova,” Regard sur l’Est, 3 November.